H | DeKalb combats the deadliest drug in the U.S.

November 6, 2017

DeKALB — Lindsey Choate, junior middle level education major, had no idea her friend had ever used heroin until it was almost too late.

“I honestly didn’t know anything about his addiction until he ended up overdosing,” Choate said. “I had no clue he was using or anything. It was kind of a shock.”

Choate’s friend, a 27-year-old man living in Mendota, had a non-fatal overdose on heroin in October of 2016. Her friend is now in a rehabilitation facility and admitted to Choate he was an on- and-off user for years.

“He was a really outgoing person,” Choate said. “Looking back, I noticed that as he started to use more, he became more withdrawn from everybody. He stopped going to classes and stopped talking to people as much.”

Heroin is a type of opioid, which are drugs that “interact with opioid receptors on nerve cells in the body and brain,” according to the National Institute of Drug Abuse.

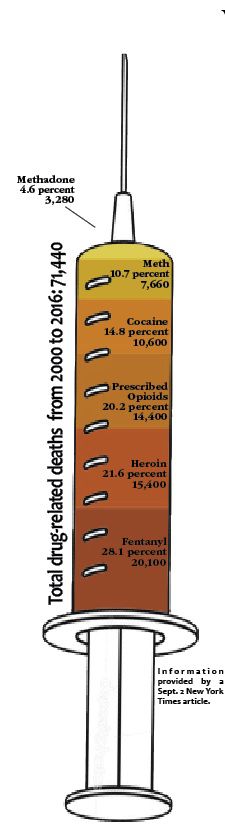

In DeKalb, opioid-related deaths doubled from six in 2015 to 12 in 2016, according to statistics from the Illinois Department of Public Health. This increase is also seen nationally, as the number of opioid deaths in the U.S. increased by 34 percent from the year prior and accounted for 78 percent of all drug related deaths in the nation

Steve Lekkas, DeKalb Police Department commander of the patrol division, said the police department’s handling of heroin-related arrests and deaths is something officers rarely had to deal with until the past few years.

“I’ve been working on narcotics cases for many years, and when I first started, there really wasn’t a heroin issue at all,” Lekkas said. “Now, it’s made a tremendous comeback in the last five years.”

Jeff McMaster, Deputy Fire Chief of the DeKalb Fire Department, said the spike in heroin caught the attention of the DeKalb Fire Department for the fact its prevalence is on the rise with no sign of stopping.

“Usually, heroin has always been in the background, and all of a sudden that spiked,” McMaster said. “The problem is that it’s not going down. It’s just increasing, and that’s where the fire department kind of opened its eyes and said, ‘This is more of a long term issue than just a recreational drug use probe.’ ”

The increase in Chicago, its suburbs and eventually counties all over northern Illinois can be traced to the growing number of suburban residents traveling to the west side of Chicago via Interstate 290. Lekkas described the interstate as now being termed the “Heroin Highway,” and residents of DeKalb are able to reach it by way of Interstate 88.

Lekkas said a trip down Interstate 290 is no longer needed to get heroin.

“With the suburbs moving out more, there have been a lot of suburbs, some of the more affluent suburbs, have had heroin epidemics for years,” Lekkas said.

The most common combattant of heroin overdoses is the medication Naloxone, or Narcan. Narcan was approved as an overdose reversal by the Food and Drug Administration in 1971.

The DeKalb Police Department receives doses of Narcan from the DeKalb County Health Department. Each squad car now carries two doses of Narcan.

“What it does is when you administer Narcan, it blocks the opioid antigens from hitting the receptors, therefore knocking out or preventing the high or respiratory depressant,” McMaster said.

Narcan has saved many lives, but the epidemic has brought weaknesses to Narcan, as synthetic drugs have become more powerful.

“Typically, in years prior, you might have been able to bring someone back with one dose of Narcan,” said Kelly Sullivan, DeKalb Police Department community relations officer. “Now we’re seeing some people need two, three or four doses of Narcan in order to bring them back. So the drug that’s out there is getting stronger than what it used to be.”

The rise in the use of Narcan has led to an extreme price increase. Evzio doses, a Naloxone auto-injection medication, that cost $690 in 2014 were worth $4,500 in 2016 — an increase of over 500 percent, according to a Dec. 8 New England Journal of Medicine article.

While the use of Narcan has increased in counties all over the nation, DeKalb police officials started a trend other Illinois counties have followed: charging heroin and opioid dealers linked to overdose deaths with drug-induced homicide.

Daniel Schak, 21, of Crystal Lake, was the first person charged under the statute in DeKalb after selling heroin to Bradley Koch, 18, of Kirkland, who overdosed and later died at the Kishwaukee Community Hospital on Feb. 15, 2004.

“As far as some of the stuff we’ve done on investigative ends, in our county, we did some of the earliest drug overdose cases within the whole state,” Lekkas said. “Going back to 2004 or 2005, we did one of the earliest drug-induced homicide prosecutions.”

Lekkas said initiatives like this reflect the way in which the police department has made removing drug dealers from the community a priority.

“When we identify that there is a heroin dealer in the area, we try and target that because it becomes a priority to either get that person off the street or get them to stop selling right away,” Lekkas said.

The department has tracked down various levels of dealers, including dealers tied to the Sinaloa Cartel, a large mexican drug cartel ran by Joaquín Loera, better known as El Chapo. The bust of the Sinaloa Cartel that took place in 2014 resulted in the seizure of six kilograms, or 13 pounds, of heroin, Lekkas said. The drugs’ street value added up to $1.4 million, according to a Nov. 22 DeKalb Police Department press release.

“We’re in a small community, but, obviously, a huge organization was here and set up shop,” Lekkas said. “That’s a federal prosecution that’s still ongoing.”

The DeKalb Police Department is not just focusing on the dealers in and around DeKalb County; officials have also been developing a program to connect opioid users to rehabilitation centers if they reach out to officials for help.

“We don’t have any facilities in DeKalb County that treat opioid addiction,” Sullivan said. “We have to reach out to several other communities that do have treatment centers in order to partner with them.”

The program is still in its early stages, but Sullivan has been working on the project and creating the connections to help rehabilitate those in need, Lekkas said.

“We’re still trying to get the logistics of it taken care of first, and then from there we’re going to try and launch it on a trial period before we start bringing in other county agencies,” Lekkas said.

Heroin overdoses do not just affect the friends and family of the overdose victim, but the first responders of overdoses like McMaster. McMaster said when firefighters see the affects the overdoses have on the families, it hits home.

“Police officers and firefighters are family people just like everybody else,” McMaster said. “When you see children living in that situation, where they are living in a home of squalor and their father or mother have overdosed…that really hits home. It really pulls your own emotional strings.”