H | Lawmakers face public health crisis

November 13, 2017

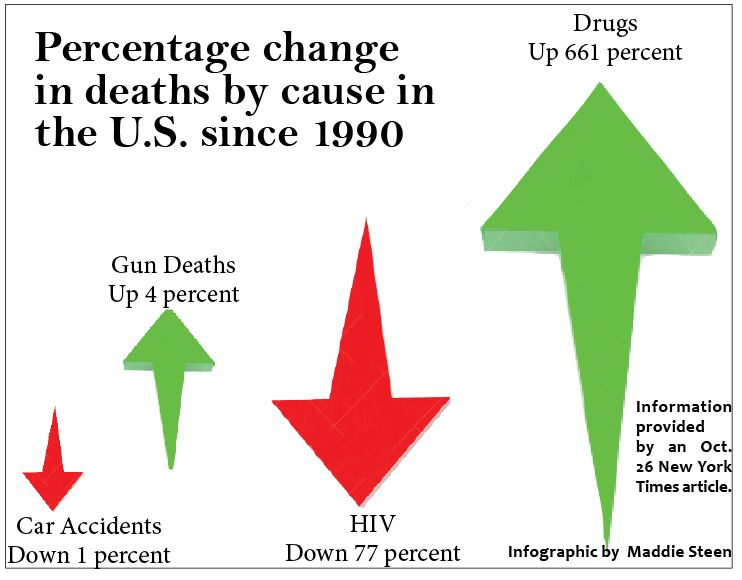

In 2016, drugs killed 64,000 Americans — more deaths than gun violence, car crashes or HIV caused in a year at their respective peaks. In this two-part series, we look at how DeKalb first-responders and state lawmakers are fighting the opioid epidemic in America.

DeKALB — For U.S. Congressman Randy Hultgren (R-Illinois), his battle against the opioid crisis in the state and in the nation is a bit more personal than most.

“I have some very personal connections,” Hultgren said. “Me and some people were at a funeral for a friend whose son had overdosed and died a few years ago. He pulled me aside and said ‘I wish my son could have stayed in prison.’ That was his only hope for not overdosing.”

Last year, Illinois had 1,964 opioid deaths, according to a Nov. 2 Illinois Department of Public Health report — an increase of 32 percent from the year prior. McHenry, Hultgren’s district, had 49 opioid deaths last year; the city is among the highest number of overdose deaths in northern Illinois.

Hultgren decided to take initiative in 2014 with the Community Leadership Forum on Heroin Prevention in Geneva, Illinois. At the panel, local and state law enforcement officers, elected officials, educators and treatment providers came together to “share resources and ideas to tackle the growing threat of heroin addiction and opioid abuse in northern Illinois,” according to a 2014 summary report on the panel.

“I think it’s been incredibly helpful,” Hultgren said. “We got some really good ideas out of this that we’re continuing to figure out, continuing to talk about action steps of how do we navigate what we’re looking for.”

Hultgren said since the panels were so well received, he has continued to hold the meetings, including one that occurred over the summer with DeKalb’s first responders.

“Those types of meetings included the coroner, law enforcement from all over northern Illinois just to get our information transferred to a national perspective,” said Steve Lekkas, DeKalb Police Department commander of patrol. “Congressman Hultgren has done a great job setting up these meetings.”

Through the panels, Hultgren has set action plans in reports, providing an original report in 2014 and an updated one this year. With the 2016 passing of the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act, or CARA, Hultgren used the forums to find out how the bill can improve life in his district and where there is still room for improvement.

“There is not one way to break the addiction,” Hultgren said. “Certain people are going to need different courses of treatment, and that’s where we can bring the right people together.”

CARA is a bill passed by Congress that allows the attorney general and secretary of health and human services to award grants to “address the national epidemics of prescription opioid and heroin abuse,” according to Hultgren’s 2017 report. Hultgren believes the problem is long from solved, but bills like CARA are a start.

“It’s been very helpful, but it’s still a process,” Hultgren said. “I don’t feel like we’ve solved the problem by any means, but I’m excited that lives have been saved.”

Illinois lawmakers trying to educate public on addiction

An issue that is being addressed in Illinois is the process of educating the public about the opioid crisis. Illinois House Bill 3161 was passed Sept. 8 and requires the Illinois Department of Human Services make a website about the epidemic that provides information about how to spot, prevent and treat addiction, according to the Illinois General Assembly website.

The bill was co-sponsored by 32 house representatives, including State Rep. Bob Pritchard (R-Hinckley).

Pritchard said the Illinois General Assembly has passed various bills related to the opioid addiction crisis as part of a three-step plan of attack for the Department of Human Services, which Pritchard said focuses on “prevention, treatment and response.”

Pritchard said part of the process in educating the public is removing the negative stigma surrounding addiction.

“There needs to be some public acceptance of the notion that drug addiction shouldn’t be as stigmatized as it is,” Pritchard said. “If we take away some of the social pressure, maybe more people would get treatment and would avoid a lot of the overuse and overdosing.”

Pritchard said a big issue the state may face is funding the fight against opioid abuse, citing recent financial issues in the state. Pritchard said there is potential for resistance on spending that lawmakers will have to work around.

“Obviously, the state is in a huge financial hole,” Pritchard said. “There’s going to be a lot of resistance even though we know opioids are a big issue. I think there would be resistance for more expenditures. We’ve got to be smart about this and see how we can leverage public and private efforts to get this done.”

The state is not alone in its opioid overdose woes. Illinois was among 19 states identified by the Center of Disease Control and Prevention to see a “statistically significant increase” of opioid overdose deaths from 2014 to 2015. With the numbers rising all over the country, the federal government has intervened.

Federal government taking action against crisis

Eric Hargan, acting U.S. Health and Human Services secretary, issued a statement Oct. 26 declaring a nationwide public health emergency at the request of President Donald Trump. This means the Trump Administration can now “accelerate temporary appointments of specialized personnel to address the emergency” and “work with the Drug Enforcement Administration to expand access for certain groups of patients to telemedicine for treating addiction,” according to an Oct. 30 PolitiFact article.

The order lasts 90 days and can be renewed by the president for as long as he see’s fit, according to an Oct. 26 CNN article.

Trump’s original plan was to declare a national emergency on the opioid crisis, which would have led to more funding for the issue from the Federal Emergency Management Agency. However, Trump Administration officials told reporters that the national emergency label “would not be a good fit for a longtime crisis,” according to an Oct. 26 Washington Post article.

Some democrats criticized the move, saying the president needs to dedicate more emergency funding.

“America is hemorrhaging lives by the day because of the opioid epidemic, but President Trump offered the country a Band-Aid when we need a tourniquet,” said U.S. Senator Edward Markey (D-Massachusetts) in an Oct. 26 New York Times interview.

While some like Markey are calling for more, supporters of the move like Hultgren said the declaration opens the door for further discussion at a national and federal level.

“I think it was a good step the president and the administration made,” Hultgren said. “I do think it does open up more opportunities for some other additional funding.”

Local law enforcement groups say that any type of funding they can get will help them begin to battle harder against the opioid addiction crisis.

“Any attention that can be brought to it and any additional resources that can be put toward it, it can only help” Lekkas said.