Seed corporation is a bully in court

July 12, 2011

In 1901, John F. Queeny decided to start a business that would manufacture artificial sweetener. Queeny named his company Monsanto, after his wife. Today, over a hundred years later, this Fortune 500 company has over 30,000 employees and over 500 facilities worldwide. Monsanto is no longer known for distributing artificial sweetener. Instead, they are the leading producer and supplier of genetically modified seeds and the popular weed-killer, Roundup.

However, Monsanto’s past isn’t exactly a bed of roses.

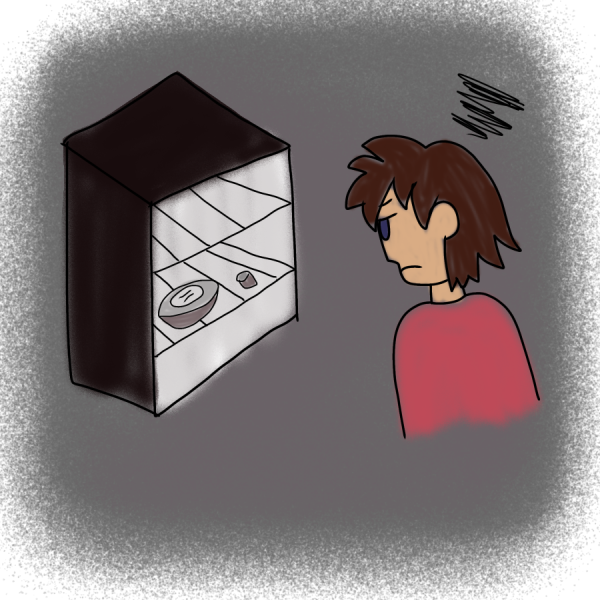

For generations, farmers have saved seed from year to year. They would plant their crops in the spring and harvest them in the fall. Afterwards, they would collect any remaining seed in the fields, clean it and store it for the following season.

Today, Monsanto has strict regulations against this practice because they have a patent on their GM (genetically modified) seeds. Farmers who sign a contract with Monsanto are not allowed to save seeds. This is so Monsanto can keep selling their seeds to farmers at a premium each year.

If a farmer is found to have Monsanto’s GM seeds on their property, whether they saved seed from a previous year or they were blown over from a neighboring farm, they can still be sued for “patent infringement.”

“Patents are necessary to ensure that we are paid for the investments we put into developing these products and to help foster innovation,” said Monsanto representative Thomas Helscher. “Without the protection of patents, there would be little incentive for privately-owned companies to pursue and re-invest in innovation.”

According to Monsanto’s website, “Monsanto and its subsidiaries (including Asgrow® and DeKalb®) currently own more than 400 separate plant technology patents. Agricultural companies such as Monsanto are able to patent seed trait technology because it is considered intellectual property, and intellectual property rights are protected in the U.S.”

Since 1997, Monsanto has filed 146 lawsuits for “patent infringement,” Helscher said.

According to an article in the Columbian Missourian, this happened to farmer David Brumback and over 100 other farmers. Monsanto filed a lawsuit against a farm co-op in 2008, stating that the co-op was cleaning seed and storing it for future seasons. Monsanto named over a hundred farmers, including Brumback, in a subpoena asking for their sales records for the previous five years. Lawyers for the co-op stated that Monsanto used bullying tactics to make an example of the co-op. One of these tactics was to make the court case drag on, so farmers would either spend hundreds of thousands of dollars on lawyer’s fees or they would settle out of court.

According to a Vanity Fair article in 2002, Gary Rinehart was approached by Monsanto investigators at his workplace where they accused Rinehart of illegally planting and saving Monsanto’s GM seeds. Rinehart wasn’t even a farmer or a seed dealer. He owned a small town country store in a tiny farming community in Missouri.

According to Monsanto’s website, “As part of the lawsuit, Monsanto attorneys filed an affidavit stating that investigators had observed Gary Rinehart driving a pickup truck used to transport the saved seed. Gary Rinehart refuted this allegation. We conceded this point and determined that his nephew, Tim, was the person who planted the saved seed on Gary Rinehart’s land. We dismissed the case against Gary Rinehart.”

In a more recent lawsuit, 83 plaintiffs–representing farmers, seed businesses, agricultural research organizations and environmental groups–filed a lawsuit on June 1, 2011 against Monsanto.

“Our clients don’t want a fight with Monsanto, they just want to be protected from the threat they will be contaminated by Monsanto’s genetically modified seed and then be accused of patent infringement,” said Daniel Ravicher, Public Patent Foundation (PUBPAT) executive director, in a press release issued by the Center for Food Safety.

Later, Monsanto issued a statement that they would not sue those who had trace amounts of their seeds on their land. “Monsanto has stated to the plaintiffs and publicly that the company does not and will not pursue legal action against a farmer where patented seed or traits are found in that farmer’s field as a result of inadvertent means,” Helscher said.

However, according to the Center for Food Safety, when the PUBPAT wrote Monsanto’s attorneys asking that the statement be made legally binding, Monsanto rejected the request. Instead Monsanto hired former solicitor general, Seth Waxman, who stated that Monsanto can make claims against farmers who become contaminated with Monsanto’s GM seeds.

These lawsuits are just a few examples of Monsanto’s aggressive tactics taken against farmers. Most of the lawsuits were settled out of court, to avoid pricey lawyer fees. Monsanto claims to be all about helping farmers and solving world hunger, but after looking at its past legal battles, it shows a different story. Monsanto seems more concerned about profiting from its technology by intimidating and accusing poor, innocent farmers. Also, if Monsanto really wanted to solve world hunger, why does it require farmers to destroy perfectly good seed instead of saving it for the following season? If you ask me, it’s all about money.