International student: The US election process is bizarre

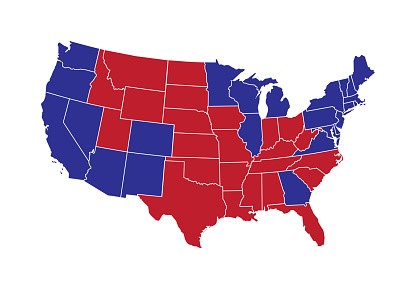

2020 Election Electoral College map.

November 30, 2020

As someone who was born and raised in a different country and spent just over half her life in the U.S., once in a while, I can’t help but compare my home country to the country where I live. Looking from the outside in, I recognize there are many similarities but there are also distinct differences. One of those being the variances in the election systems and how we end up with such different results, politically speaking. The most unique difference is the use of an electoral college in the U.S. and it seems fairly outdated.

The “Founding Fathers established [the Electoral College] in the Constitution, in part, [as] a compromise between the election of the President by a vote in Congress and election of the President by a popular vote of qualified citizens,” according to a 2019 National Archives article.

Based on the century-old Magna Carta established in 1215, the U.S. Constitution we still live by in 2020, reflects how the old British democracy was interpreted in the 18th century, according to an October Encyclopedia Britannica article. While it has been changed and adapted over the years, it has not kept up with modern times and the changing face of the nation, redefining who is a “qualified citizen.” The Electoral College is a leftover relic from a time when the U.S. looked quite different.

Since I am most familiar with the German election process, let’s take a look. The Weimarer Republik, a predecessor of Germany’s current democratic system, was only short-lived and didn’t survive, leading to a dictatorship and the worst world war in modern history. It wasn’t until after WWII that Germany got a fresh start with democracy and it was understood that in order for a country to prosper and thrive, it needed a stable yet adaptable form of democracy that would listen to its people and never again allow someone like Hitler to seize power.

This is something that has not happened here: While the U.S.’ society has evolved, the political system has not kept pace and in essence, we live in an 18th century framework with 2020 modernism. With every election, the divide seems to deepen and one can only explain it this way: The idea of a “winner takes it all” approach is simply outdated and divides rather than unites. And how could it be any different when almost half the country feels unrepresented at every election?

Maybe the time has come to reconsider the electoral college and the way elections are won. Germany’s way of learning from the past resulted in a constitution that established a so-called representative democracy that created a 5% hurdle. This means any party with 5% or more of the popular vote gets a seat at the table. Since there are more than just two parties, a compromise must be made in order to get anything done. According to Tolulope Bello, an international student from Nigeria, it seems that this may not be the norm though. She says while the American system “it is quite confusing” using an electoral college, the popular voting system in her country still results in a winner-takes-it-all situation.

For simplicity’s sake, Germany’s election process can be summed up like this: each voter has two votes. Since people do not vote for the chancellor directly, one of those votes is used to elect the party that will bring the chancellor into power. The second vote is used to send representatives of their own state to the so-called Bundesrat. The votes don’t have to go to the same party and can be split up any way desired. This means each of the 16 federated German states can have a different party represent its people while the chancellor is of a different party. Instead of primaries that decide on only one candidate that will go on the ballot, voters can choose from a long list of representatives of each party. Again, the winner-takes-it-all approach does not exist and therefore yields a fairer representation of the people’s voices and wishes.

An NIU student from Southeast Asia explained that the voting process in her country is different and yet somewhat similar to Germany’s in that each province votes on representatives who then go to parliament. The person in power and running the country is very much like the German chancellor or the American president.

So, here in the U.S., we have to sit by while one candidate after another from the party we identify with the most is eliminated during the primaries. All the voices of others we casually dismiss in the process are people who are not properly being represented. The way I have observed it in the last 20 years, disenfranchised voters often don’t come back around but take the hard stance of “I want my candidate to win or I won’t vote at all.” It’s a dangerous and slippery slope and the only way I see a solution is to find a better way to represent all. How is it possible that a president can rule when less than half of the country supports him, winning solely because of the electoral college’s votes?

What we have here then, in the U.S., is a “democracy” that pits one against the other instead of truly uniting us by listening to all. Many of our voices go unheard, causing frustration and disengagement. I don’t have a clear solution but offer the idea of abandoning the old practice of using an electoral college is a good start.