That Time I… snail-paced a ski race

Opinion Columnist Lucy Atkinson shares a story about an unfortunate high school ski race.

November 4, 2022

Throughout high school, some of my fondest memories are traced back to time spent on the cross-country skiing team.

One clarification must be made, however: while I skied competitively for seven years, I acquired very little glory.

Clumsy, slow and uncoordinated, I adored skiing for the friends it brought me. Competition was not my strong suit.

Thus, freshman year, when my coaches placed me on the State’s relay team simply because they needed a fourth girl in order to compete, I knew I was in for an embarrassing afternoon.

The day of the race, skiers were lined up behind the starting line. Racers with a history of quick times were placed in front, so I stood shaking from nerves and the cold at the very back of the mass.

The flag was raised, it came crashing down, and every racer in the competition flew out of sight. Every racer, that is, except the 5-foot-9 14-year-old with the unfortunate habit of tripping over her ski-poles.

Still, this was not my first race, and I had developed several tactics over the years to help myself get through a course. Singing songs to myself was one such habit, as well as muttering a classic phrase about the force, whenever flying down a large hill.

It turns out indulging in one’s love for Star Wars is an effective method of calming race-nerves.

The other racers remained kilometers ahead of me and the hundreds of cheering and cow-bell-wielding spectators had, understandably, followed them. I was completely alone on the trails. I could therefore afford to sing my songs and summon the force to my aid quite loudly.

Eventually, numerous falls and long struggles to untangle my skis later, I finally reached the end of the course. As I passed the finish line, to the relief of both myself and the race-managers anxious to begin the next event, I found I felt better than I had expected to.

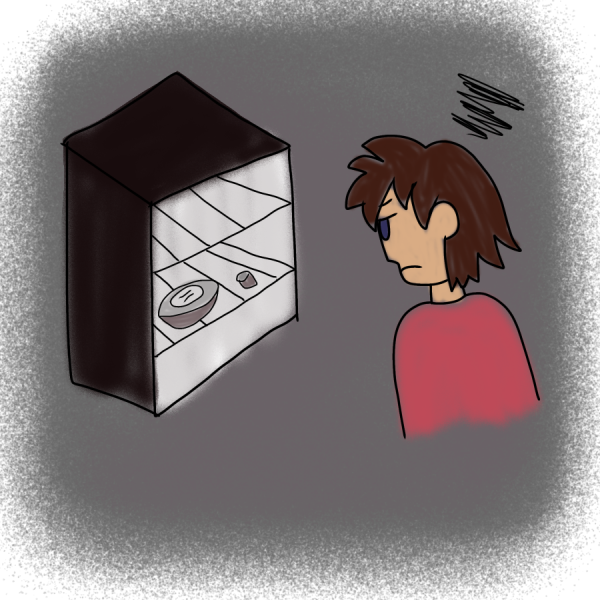

I had failed massively, but my sweet teammates and coaches had cheered me to the finish, hugged and reassured me, and there was a peanut butter and jelly sandwich waiting for me inside. The afternoon was ultimately a win.

Since that day, I’ve failed countless more races; but with each year, the place I got mattered less. Senior year, as I painted my friends’ faces with glitter, a competition-day tradition, I realized no disastrous race could ever have kept me from the team that brought me so much joy. I hugged the new freshman, embarrassed of their own races they considered failures, and I wished them the same revelation.