Genetic editing should slow down

February 28, 2019

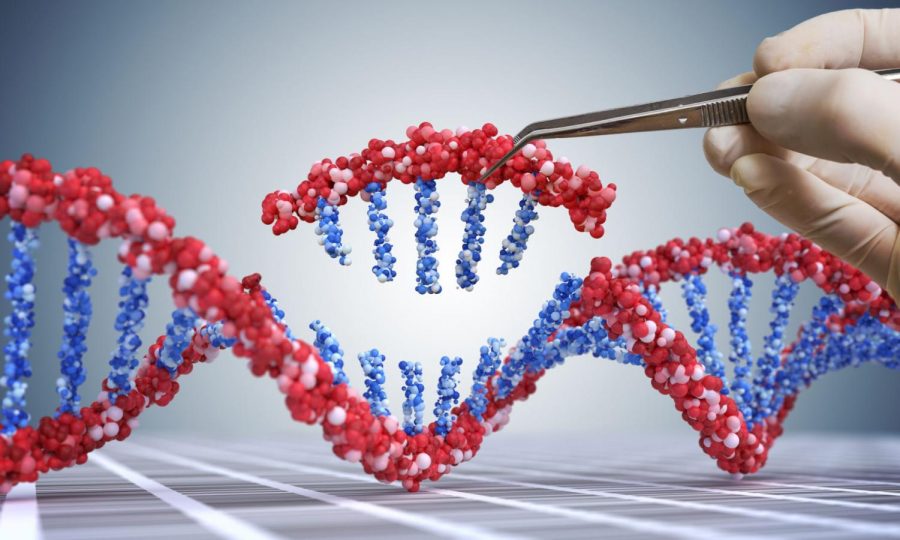

Genetic manipulation technology, straight out of science fiction, is fast approaching, bringing along the possibility of eradicating genetic diseases from the human genome —but maybe we should slow down.

In November 2018, scientist He Jiankui used gene-editing technology to create HIV-free twin girls from an HIV positive father. He’s research is unpublished in scientific journals and received backlash from his peers, according to a Nov. 26 NPR report.

There’s a lot to unpack in He’s experiment. First and foremost, there’s no consensus in the scientific community on whether gene editing human embryos is an acceptable practice. Embryos can’t consent, for one, and modifying our DNA may wander too close to playing God. Scientists are currently trying to puzzle it out at events like the International Summit on Human Genome Editing, first held in 2015 in Washington D.C.

Also, nothing is known about the long-term effects of human gene editing. There is genuine worry over DNA modifications causing unforeseen consequences down the line, and there is little way to uncontroversially research it until the ethics behind the technology get nailed down.

To avoid the ethical concerns, Dieter Egli, a developmental biologist at Columbia University, has been testing gene-editing technology on embryos and then stopping their development after day one, according to a Feb. 1 NPR report. His hope is to find a cure for an inherited form of blindness called retinitis pigmentosa.

Even if stopping embryo development avoids the outcry He faced, the question of whether such a cure would be ethical remains. Philosophy professor Jason Hanna said the concerns multiply for research of this nature.

“The first time [this technology] is used, it would be a kind of research that comes along with all kinds of medical ethics,” Hanna said. “This gets very difficult to apply when dealing with children because most of us think young children can’t validate consent, and it gets even harder when dealing with embryos.”

Embryonic consent is clearly impossible, but that doesn’t settle the debate outright. Many of the possibilities opened by the research are brilliant and utopic — a world free of genetic disorders like the blindness Egli is focusing on.

But then come the other, scarier possibilities.

“In principle, if you could use genetic editing techniques to get rid of genetic diseases, you might be able to use them to enable people to edit in desirable traits,” Hanna said.

Hanna said enhancements are what people are most worried about. When enhancements become possible, the vision quickly turns dystopic. The free market can’t be left to regulate the technology — only the wealthy can afford to enhance their embryos, perpetuating inequality. The government, which is currently struggling to avoid another shutdown, couldn’t afford it either.

“As long as you don’t go too far [gene-editing is OK],” Michael Peterson, junior computer science major, said. “If you try to make it so people can hear as good as dogs, then you’re getting to the part where we don’t quite know what other repercussions it could have.”

So, the solution seems clear, if difficult to implement: Figure out how to heal the genetic diseases, but don’t go any further.

Even so, interested private individuals may try to figure out enhancement methods. In fact, the university where He was employed said his research was not sanctioned by the university nor conducted on campus, according to an official statement released Nov. 26, 2018.

He’s and Egli’s work represent different approaches toward the new horizon opened up by gene-editing technology. On Egli’s side, we have the slow, methodical approach toward safe and scientifically accepted research; on He’s side, we have the risky, ethically questionable leap to modified babies.

Take Egli’s side on this: no more leaps until this technology has been figured out, long-term effects and all.