When Lauren Threatte, DEI Postdoctoral Fellow with NIU’s College of Law and WGS department, went to get her IUD inserted, she was warned of mild pressure during the procedure. The actual pain, however, was among the worst she’s ever felt.

A form of long-term birth control, the IUD – or intrauterine device – is available for those with a uterus, but the lack of pain medication available for patients is a clear example of medical sexism. It’s time providers are honest about pain like Threatte’s and work to relieve it.

“Once it was in, it was uncomfortable. From the moment I had it into the moment I got it taken out, it was painful. It felt like someone had pumped me up with something, and it was just like sitting on my cervix,” Threatte said. “I remember just being in pain on the bus (after the procedure), just sitting there, like: ‘What did I just do to myself?’ And they (medical personnel) were like: ‘Well, it might be uncomfortable for like a week or so but it will get better after that.’ Well, that week never came.”

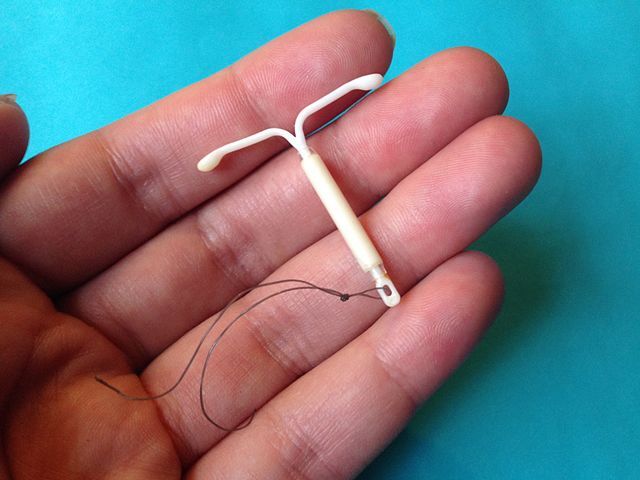

Shaped like the letter T with two long tails of string, IUDs are about the size of a quarter and come available in two forms: copper and hormonal. Once inside the uterus, hormonal IUDs halt ovulation, copper IUDs deter sperm and the devices can last 3 to 12 years before removal is necessary, as outlined by Planned Parenthood.

With a pregnancy prevention rate of 99%, the IUD is growing incredibly popular. In 2020, 65.3% of women were using contraception, and of that total 10.4% were using a form of long-term reversible contraception – such as the IUD, according to the CDC.

However, empowered conversations about the female reproductive system never get to thrive, it seems, without the intrusion of controversy and sexism.

As the Washington Post termed it in a stunning reflection on female pain, medical sexism exists today in many cases as the gender pain gap: the brutal younger sibling of the gender pay gap.

It’s a reality people have battled for decades and is especially prevalent for women of color and the transgender community.

“There’s been studies that have documented that women are often treated as hypersensitive to pain, and Black women especially are expected to just tolerate pain,” Threatte said. “They expect you to just be able to suffer through it because ‘you’re strong, you’re supposed to be stronger than other women, so you should just deal with it.’”

However, it’s a rare person who finds the sharp insertion of a plastic device into their uterus tolerable. Especially when that person is without pain medication, fully conscious, entirely vulnerable, nervous and unaware of what’s to come.

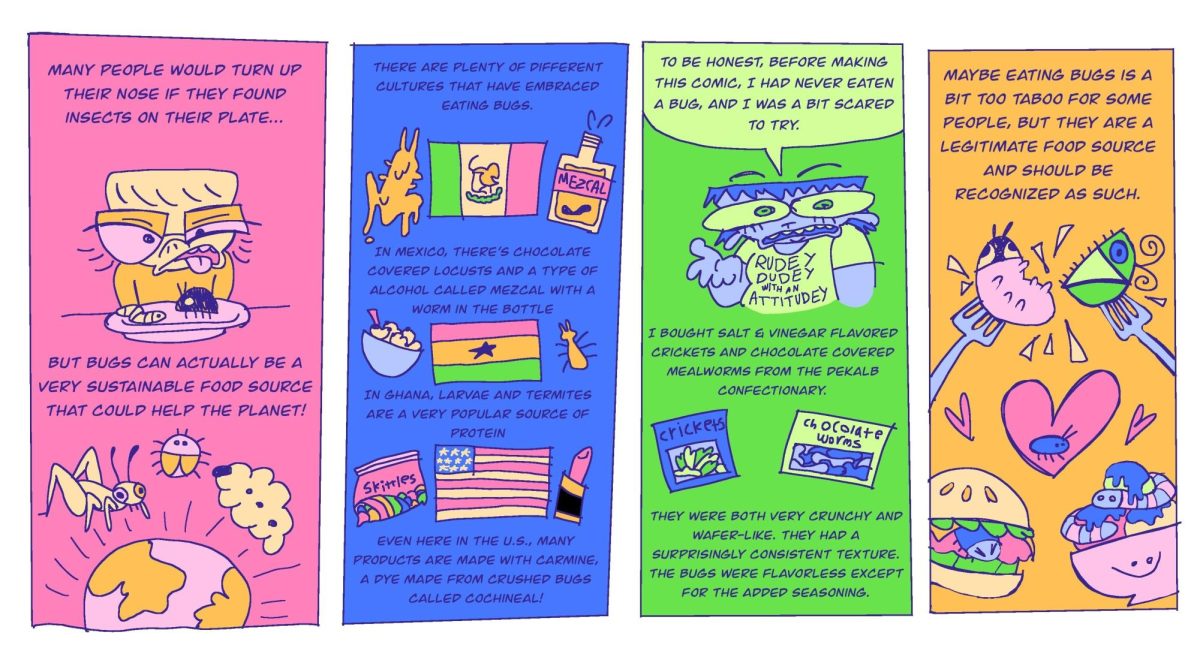

Social media, especially TikTok, has proved to be a powerhouse for people speaking about their experiences with the IUD insertion. Many patients have described the process as the most excruciating experience of their life, describing incapacitating cramps during and after the procedure, light-headedness, bleeding and nausea.

In the U.K., a Change.org petition to improve pain relief for the IUD began in 2021, received 35,000 signatures and prompted hundreds of patients’ to share their severely painful IUD insertion stories.

Furthermore, an American study published in the journal Contraception found that the pain patients experience is underestimated by providers for this procedure. On a scale of 1 to 100, patients ranked pain at 64.8 on average, while providers only ranked pain at 35.3 on average.

Patients have also reported dishonesty from providers about how their experience getting an IUD will be, with clinics merely warning they’ll feel some discomfort. Others have reported being told they’re being overdramatic when they express pain or that they need to calm down.

“The doctors, they were still unempathetic, they minimized my pain, minimized my complaints, gave me absolutely no autonomy in making the decision,” Threatte said. “I actually vocally screamed – and I’m not a screamer, I can’t remember ever screaming really at anything. And I almost felt bad about it because they were kinda acting like I was exaggerating.”

Threatte also suffered an additional side-effect doctors failed to warn her about: hyper-pigmentation of the skin, permanent damage to her skin. Eventually, after about four months of pain, Threatte decided she must get the IUD removed.

“Every time I look in the mirror I’m reminded of the IUD,” Threatte said.

Threatte’s experience was traumatic, excruciating and not at all uncommon. Change is obviously necessary, so what needs to happen?

The spread of awareness that’s surfaced on social media and through news coverage is good. Telling stories and sharing our unique experiences with the IUD procedure makes it easier for those preparing to undergo it.

But there are other ways to physically ease the pain patients feel during IUD insertion, such as lidocaine-prilocaine cream – think numbing cream and cervix blocks – basically a local anesthetic injection, according to a 2020 study published in the National Library of Medicine.

Anecdotally, however, it seems these options just aren’t being implemented.

For instance, while patients are almost always offered sedation for colonoscopies, few clinics offer sedation for the IUD, as noted in a Harvard Law, Bill of Health reflection on disclosing pain in the medical field.

Such pain relief should not remain so unique. It should be far less difficult for uterus-owners to find clinics which offer and popularize these options.

Furthermore, providers must be exhibiting compassion, patience and honesty when discussing the IUD and while actually performing the insertion.

If you’re due to get an IUD, research the procedure ahead of time and plan to have at least two days of rest following the insertion. Ask your doctor about further pain management techniques and side-effects and advocate for yourself. Be honest about your nerves – if they’re shamed or put down, it’s time to find a new clinic.