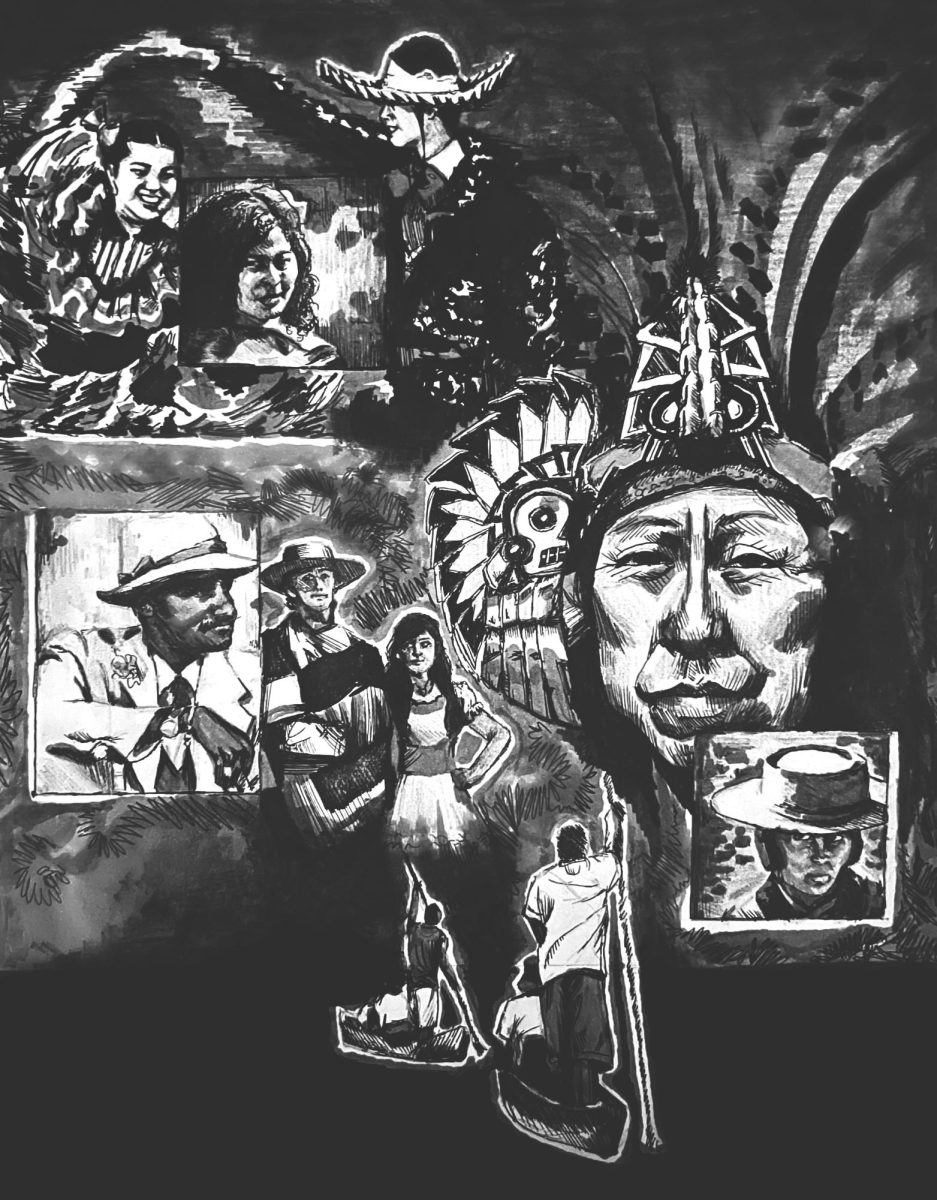

For decades, a guerrilla group known as FARC-EP, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia or the People’s Army, terrorized Colombia. I was born in 2003, at the height of the conflict, when the FARC and paramilitaries reached the pinnacle of their military power.

Horrible attacks occurred during the FARC’s conflict with the Colombian government, such as massacres, bombings and skirmishes. However, many peace processes, or attempts to create peace, also took place.

Protests and rallies in favor of a peace agreement had stirred up, not just against FARC, but also against other guerrillas, paramilitary groups and cartels that existed and still exist in Colombia.

In the 2010 presidential election, Juan Manuel Santos, who was a presidential candidate at the time, broke the political establishment of that year by promising to sign a peace agreement with the FARC at one of the most critical points of the conflict.

He won the presidency, and in 2012 began that peace process.

Meanwhile, I was a child watching the results of the bombings and skirmishes in the most remote corners of the country on the news every day.

I never lived near the front line, but that never made me ignorant of what was going on.

My school was near the airport of the military air transport command, so every two weeks in the afternoons it was common to see fighters or attack helicopters flying over the school.

My school constantly canceled classes because there was a “public order situation.” A public order situation could mean that a bomb exploded or that a protest turned into a battle in the city.

It could also mean what in Colombia is called “paro armado,” which means guerrillas had started closing vital roads and were shooting at vehicles trying to pass through the blockades.

Discussions about the peace process were common in my family’s dining room whenever FARC carried out an action that endangered the continuation of peace talks.

One of the most serious incidents, and the one I remember best happened on April 14, 2015. That night, troops of the Apollo Task Force, a military special unit organized to a specific task, which was counter-guerrilla at that time, were ambushed by the mobile column “Miller Perdomo” – a force organized by FARC.

There was a bilateral ceasefire in force at that time, so the soldiers were not alert and there was no guard. They were camping on a lighted soccer field.

The guerrillas did not just attack with rifles, they used grenades and homemade explosives.

The military did not even have a chance to return fire. Eleven were killed and 20 others wounded.

This incident was one of many that disrupted the struggle for a peace process.

Finally an agreement was reached. In August 2016, it was announced that the government and FARC had finished drafting a peace agreement and that a plebiscite would be held for all of Colombia to ratify the agreement. A plebiscite is a popular vote called by the President on a national question.

There would be two options to vote: “yes” and “no.”

The more conservative political wing of the country decided to support the “no,” arguing with several lies, such as that the peace agreement forced schools to turn their students into trans individuals. They also argued that the war would continue regardless of the peace process.

The vote for “no” won with 50.21% of the votes, and for three weeks we all had a single thought in our heads: Now what?

The agreement had not been invalidated, but it had not been accepted and could not be enforced.

The miracle seemingly fell.

However, university students began rising in protest and camped on the central square of the capital city, Bogotá D.C.

The international community expressed its support to both sides by awarding the Nobel Prize to the president of Colombia. All the political parties met, changes were made, which were no more than two-sentence amendments, and finally the agreement was signed and implemented.

It took effect on Nov. 24, 2016, ending a 52-year war with the continent’s oldest insurgency.

I was born at the height of the war in 2003. Until 2016, I did not know any other reality than being in a militarized country.

I grew up with stories of how the conflict began, stories from my grandparents of forced displacement and family members being killed.

I matured with the stories of my parents when the country faced its darkest moments between drug trafficking and insurgencies.

No one in 2012 would ever have thought to suggest that everything would end up in a UN-backed peace process. But thanks to the young people who never lost faith and the adults who never stopped trying, peace finally happened.

The peace treaty wasn’t signed because the optimal conditions to sign had been met, but because of the persistence of those who set peace as their goal.