College students are increasingly struggling with a skill long considered fundamental to academic success: Reading. Experts, such as David Paige, a professor of literacy education at NIU, said the problem does not begin in higher education.

“It really starts during a student’s K-12 literacy experience,” said Paige. “It’s just a series of cascading events that have happened.”

Reading scores in elementary and secondary grades have remained largely flat for years and national assessments show those numbers dropped significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Reading scores across fourth grade, eighth grade and 11th grade basically remained stable,” Paige said. “Now during COVID, that number dropped by quite a bit.”

As a result, many students enter college already underprepared. Paige noted that students often arrive without meeting key reading benchmarks.

“We end up with a lot of students coming into the university who don’t read well,” Paige said.

According to ACT, Inc. the nonprofit organization formerly known as American College Testing, a score of 21 on the reading section indicates a student is reading at a late high school or early college level. It also indicates a 75% chance of earning a C or better in an introductory college-level social science course.

“What students end up having a really hard time about is, number one, reading an academic text,” Paige said. “That would be the textbook, that would be a journal article.”

Paige went on to say that students also struggle to synthesize multiple readings, a key skill in college coursework.

“If I give them two or three and I want them to synthesize that, they just can’t really do that very well,” he said. “They have a terrible time moving that content into long-term memory, and they have a terrible time talking about it because they haven’t read it well enough to start developing the language.”

Columbia University professor Aaron Ritzenberg has observed similar challenges.

“Reading long texts is a skill that can be practiced and cultivated,” Ritzenberg wrote to the Columbia Spectator in 2024. “And yet I think that skill is dwindling because the expectation that you sit with one text for a long time is becoming more and more rare.”

Paige said students bring digital reading habits into academic settings that are hard to unlearn.

“Students are bringing skimming habits to class,” he said. “They skim through a text, they look at it really quick, and as far as they’re concerned, they quote, ‘read it.’”

Attention spans have also declined, he said, due in part to constant device use.

“Kids who spent five, six, eight, 10 hours a day scrolling through devices, that really robs them of attention. They get into my class, and I want to talk about something for 20 minutes, and they have a hard time paying attention,” Paige said.

This trend extends beyond the classroom. A 2024 study published in iScience found that daily reading for pleasure among U.S. adults fell from 28% in 2003 to 16% in 2023, a relative decline of about 43%, based on data from an American Time Use survey.

Even when students can decode words, comprehension often suffers because of limited background knowledge.

“By the time kids get into middle school, high school, they generally know how to read words pretty well,” Paige said. “But so what else is driving that? Well, it’s knowledge.”

Background knowledge plays a key role in vocabulary development, helping students recognize and understand more words.

“You can’t teach that many words to kids, but you can teach what I call academic words,” Paige said.

These words appear across disciplines and often determine whether students can understand a lecture or complete a reading assignment.

“Professors have to really teach them, hey here’s how we’re using this word, because words can have multiple meanings depending on context,” Paige said.

Students who learn this vocabulary often gain an edge.

“What students understand is that ‘gee, if I learn these words and I learn what they mean and I learn how to use them correctly, I’m halfway through this course,’” Paige said.

Despite the obstacles, Paige has seen students improve with practice. One student told him she could barely read for 15 minutes without skimming. By the end of the semester, that student began to spend more time reading and gain a lot more understanding.

Paige believes that curiosity plays a major role for students’ desire to read.

“Reading is an outlet for curiosity,” Paige said. “Pretty much everybody is curious about something. People who aren’t particularly interested in reading, but they’re interested in something and reading is one way to do it.”

He added that reading frequency helps.

“If you can’t read the text 135, 140, 150 words a minute or faster, then reading is probably kind of difficult,” Paige said.

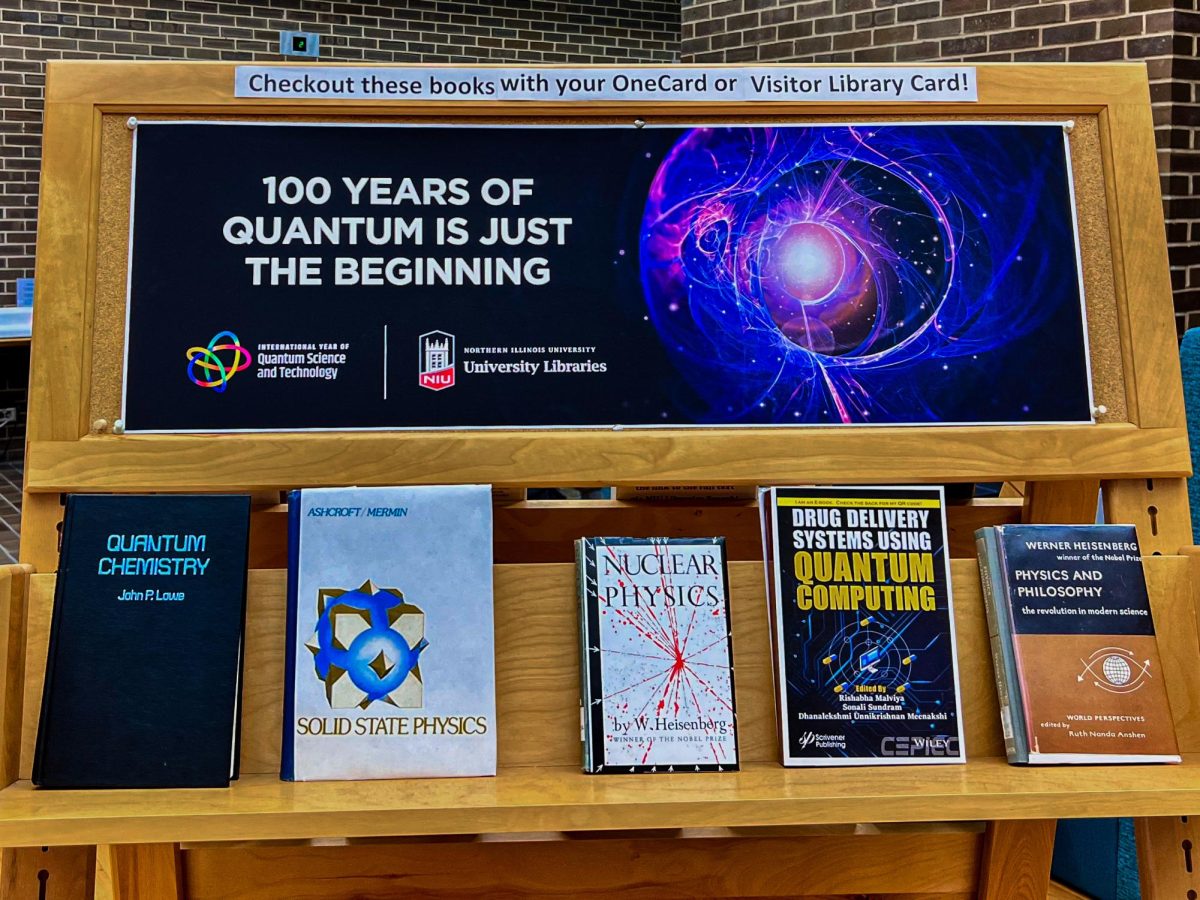

Still, there are signs of progress. The Illinois Report Card for 2024 showed record-high English language arts proficiency among third through eighth graders.

Paige encourages students to remember one thing.

“Students can improve,” he said. “They really can.”