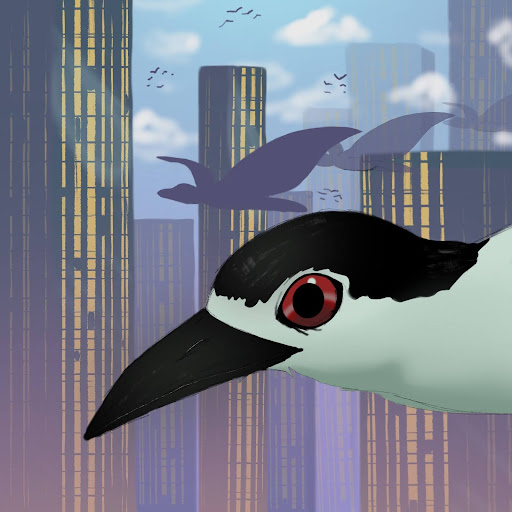

September and October are months of movement for many in the avian kingdom. Songbirds and waterfowl, colorful feathers and beige plumage, huge flocks and solitary travelers all pass overhead in one of nature’s most fascinating traditions. It’s people who add tragedy to those magnificent flights.

Millions of birds migrate across Illinois every fall. But this autumn marks the second anniversary since McCormick Place in Chicago made a critical change to counteract its deadly design.

For decades, Field Museum Ornithologist David Willard made it his mission to calculate the dreadful number of bird collisions caused by McCormick Place – dutifully collecting specimens for nearly 40 years. During that time, Willard identified more than 30,000 birds killed by collisions with the building.

In the summer of 2024, responding to pressure from findings like Willard’s, McCormick Place completed its most effective bird-safety initiative yet.

Bird-safe film – a grid-like design with dots spaced two inches apart – was implemented to the inside of the building.

The following migratory season, bird deaths related to the building were down 95%.

But finding solutions like McCormick Place’s doesn’t need to be rooted out by ornithologists alone, or take nearly half a century to happen. The danger city lights and windows create for birds is well-understood.

Bird populations are on a significant decline globally. Windows aren’t the main culprit, of course. Plenty of other interconnected human-caused issues – from climate change, to habitat loss to pollution – threaten birds worldwide, just like they threaten much of the Tree of Life. We owe our avian friends a lot more effort than we give.

McCormick spent $1.2 million on its bird-safe film installation. But the one-time fix has already prevented thousands of avian deaths and gives McCormick a good name in the environmental community.

Life for design is an unethical sacrifice that owners of large buildings – especially large buildings with prominent window coverage – should ensure their infrastructure doesn’t make. And solutions don’t have to be costly.

Jemma Waldrop, a junior environmental sciences major, spent last year working to prevent bird deaths at NIU.

Originally begun by NIU’s Inclusive Birding Club, Waldrop’s work was part of a student project that recorded bird deaths occurring across campus.

“We’d go out for migration season in the spring and fall, every morning Monday through Friday, and walk around a set number of buildings – a set path – and it would take us about an hour to make it around campus,” Waldrop said. “We’d be looking for birds that had collided with windows.”

The project found Montgomery Hall took the awful win for most bird collisions daily. To right this wrong, Waldrop’s group used inexpensive chalk markers to apply a pattern of dots, four-by-four inches apart.

“It (the dots) breaks up that kind of flat mirrored surface that is the window,” Waldrop said. “It’s really hard to tell that it is a very physical barrier (for birds), and it kind of breaks up that surface and shows you that, oh, there is actually something here. It’s not just, like, an open space.”

Light also plays a huge role in confusing migrating birds, Waldrop explained, which is the same reason McCormick Place’s bird-safety initiative includes a building Lights Out policy.

“Lights can take birds off path, can kind of attract them in, and it can tire them out,” Waldrop said. “Migrating is a really taxing thing to do. So, like, being taken off path like that, they end up tiring out, having to land in urban areas, whereas they might have previously flown through or migrated through. And then when they’re in those urban areas, they wake up in the morning, and all of a sudden they’ve got all of these reflective surfaces around them that are reflecting back.”

With its bright lights and complex infrastructure, Chicago is one of the deadliest cities in the U.S. for migrating birds. One building’s success won’t solve the problem, though McCormick Place’s installation is admirable.

Volunteer and advocacy groups – such as the Chicago Bird Collision Monitors – continue to fight for bird-safety ordinances that would require, not simply encourage, large buildings to address bird collisions. It’s overdue for Chicago’s architecture – and infrastructure everywhere – to merge compassion with design.

Fly away safe from here, feathery friends! Seeing you is only our privilege, but flying freely is your right.