Nature didn’t only hide protein in pigs and cows. The potential of insect meat as an alternative to traditional meat industries is a subject that deserves more serious investigation.

One of the largest environmental taxes of the meat industry is the space it takes up. Storing large animals – even done cramped and unethically, as so many slaughterhouses do – requires large-scale facilities. Slaughterhouses and meat farms contribute immensely to deforestation and greenhouse gas emissions.

Yet, the demand for meat will only grow as humans do. The animal-protein market is projected to increase 72% since 2013 by 2050, when our count on planet Earth will hit nearly 10 billion.

Tapping into the potential of insect meat would never replace traditional livestock methods by any means, but it could serve as another alternative – and hopefully, decrease the environmental toll of providing humans protein, at least to some extent.

Simply explained, insect farming requires less space and energy, and therefore, can hopefully be more environmentally sustainable. The method may be a moral improvement as well. To ethically raise and harvest insects is much easier because – as far as we understand at the moment – the natural necessities for a meaningful insect life require much less energy than what a cow needs to be comfortable and happy.

But among the biggest challenges for actually using this option is getting consumers – and therefore investors – on board.

Lab grown meat is too scary, insects are too gross, but eating less meat is just not possible. How does that make sense, oh so smart homo sapiens? If we can’t bite the bullet for once – or in this case – bite the beetle, we’ll eat ourselves out of options.

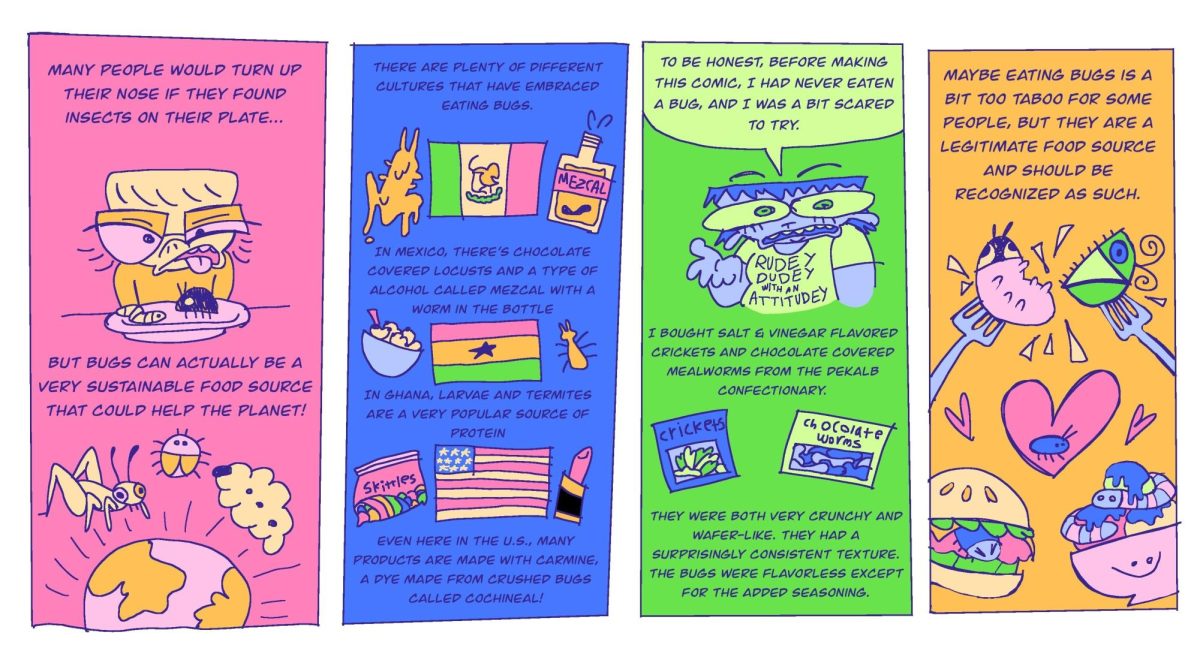

People have been eating insects for a long time, all over the world. Harvested correctly – just as harvesting any meat must be done with care – meat is meat, no matter the size or general creepy crawliness of the organism.

“The Western cultures, and like the United States, we’re kind of the odd ones out that we don’t eat insects or their related friends, and we’re missing out on an excellent source of protein,” said Ellie Taylor, an NIU alum who participated in entomological study while earning her graduate degree. “For the longest time, insects have been considered food for just about every place except for the United States and parts of Europe. It was even in the Greek times where they would have insects being eaten, and they were considered both as a delicacy and as the food for the proletariat.”

In fact, insect meat has been associated with medicinal benefits and astounding nutritional capacities. Edible insects are generally rich in vitamin B12, zinc and iron – among other helpful nutrients.

This story isn’t encouragement to take insect life for granted, but to follow suit of the countless other species that hack this awesome and fruitful wealth in the food web. Just because they’re arthropods doesn’t mean insect life isn’t valuable, and our status as predators doesn’t mean we can ditch all morals.

To make such an alternative work, the ecological impacts of harvesting insects must be intensely investigated. We’d need to ensure the meat we’re using isn’t derived from endangered species already experiencing population declines, we’d need to organize ethical and efficient breeding practices to avoid exhausting the harvested species’ regeneration capacities, and we’d need to consider the ecological impacts our farming could have.

We have a cruel habit of exploiting natural resources, so we’d need to do our homework. Currently, there aren’t a ton of options for commercial insect food products, but Taylor recommends interested consumers check out Chirps.

“This particular company specializes in a cricket flour,” Taylor said, adding that she has enjoyed Chirps foods herself. “They’ll have their cricket cookie mix. They’ve done chips in the past, but they also have protein powders.”

Cricket cookies are an awesome start, but we don’t have all the answers, and we certainly need to do more research to understand how completely this alternative could serve our species. Surely we’re mature enough not to let a possible solution go uninvestigated just because we’ve got the ick.

“One of the things that I find that helps people to kind of switch how they’re thinking on it is that they eat bugs already, most likely, right?” Taylor said. “So bugs used in the vernacular sense is basically a lot of creepy crawlies. And if you like eating crab, if you like eating lobster, if you like eating crawdads or shrimp, they are so closely related to insects. Actually, for people who have shellfish allergies, they’re not recommended to eat grasshoppers or other insect based foods because the protein that is common for the shellfish allergy, etc., is also the same protein that can be found in insects.”

House flies and cockroaches scavenge whatever sustenance they can to keep their tummies full; countless beetle species hunt and eat smaller prey, generally other insects; butterflies drink nectar, but also sweat, urine and sometimes even blood.

Insects sure aren’t picky, and they’ve been around for hundreds of millions of years. Maybe it’s time our measly 300,000 year-old species learns something from the experts.