UK censorship laws alter free speech

April 25, 2019

Recently, the U.K. proposed laws that would strictly regulate social media content. The Northern Star Editorial Board asserts that while hate has no place on social media, restricting the capacity of social media is not the solution.

A proposal for a set of laws that would hold social media companies responsible for the spreading of violent and harmful content was presented April 8 to government officials in the U.K. The laws, disclosed in the proposal “Online Harms White Paper,” would allow the British government to fine or penalize companies that fail to immediately remove violent content.

Obviously, social media is no place for this kind of graphic content, but when we force private companies to remove content, we encroach upon the rights of free speech that everyone should have.

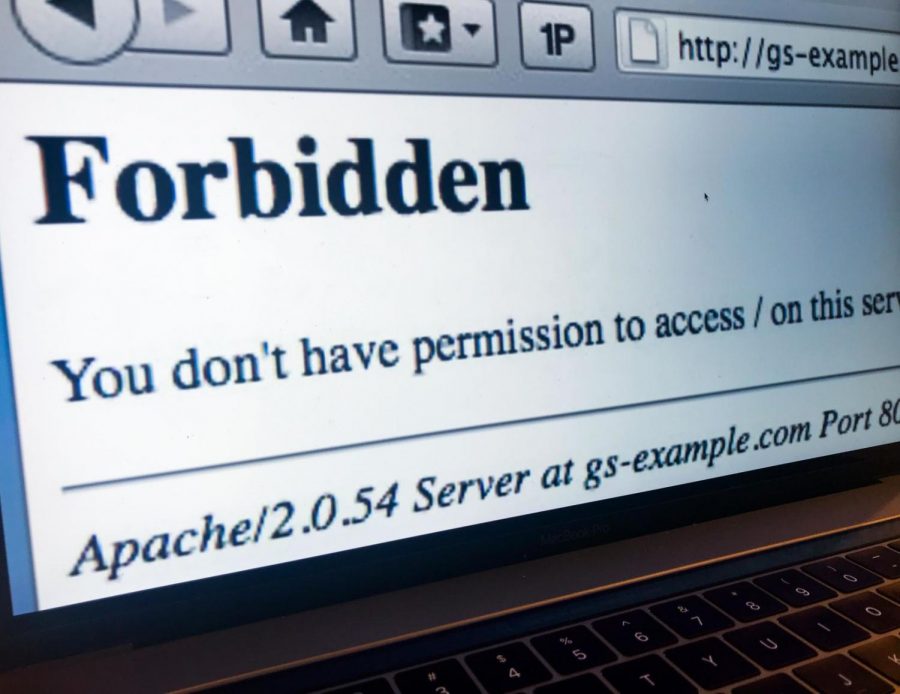

To enforce these laws, the U.K. will set up a regulatory office empowered to impose fines, block access to websites and hold company executives accountable for content.

No matter how well defined these proposed laws may be, there will always be a subjective, human element capable of cherry-picking content based on personal biases.

“It’s a balancing act,” David Gunkel, professor of media studies, said. “Free speech is not a right that is absolute. For instance, you can’t say ‘fire’ in a crowded theater. The question is: How do we direct social media providers to encourage free speech, but not hate speech?”

While the U.K.’s desire to protect children on the internet is praiseworthy, these efforts would not significantly benefit the public. Children age 13 to 17 make up just 4% of the U.K.’s Facebook users, according to Statista, an online provider of consumer data.

Another aspect of social media the proposal addresses is the concept of an echo chamber. In an echo chamber, a user is exposed to only one type of idea instead of a range of opinions. Because these ideas are never rebutted, disinformation gets promoted.

While it is important social media users have access to factually accurate content, users should be responsible for verifying the accuracy of information for themselves.

Picking and choosing which ideas get to remain on the internet is a slippery slope. When we scrub any idea we don’t agree with from the internet, we create what we set out to destroy: echo chambers.

Even though hate on social media is a major problem, censoring social media is not the solution. The burden of protecting children should fall to social media companies and parents, not the government.

“This is just the first go-around,” Gunkel said. “Even if the U.K. doesn’t get it right, law is something that finds form over time.”

In the end, the potential benefits of restricting social media do not outweigh the threat that restrictions pose to individual freedom. For better or worse, social media has taken hold of our society and become a platform for love as well as hate, but hate doesn’t come from the internet; it comes from us.