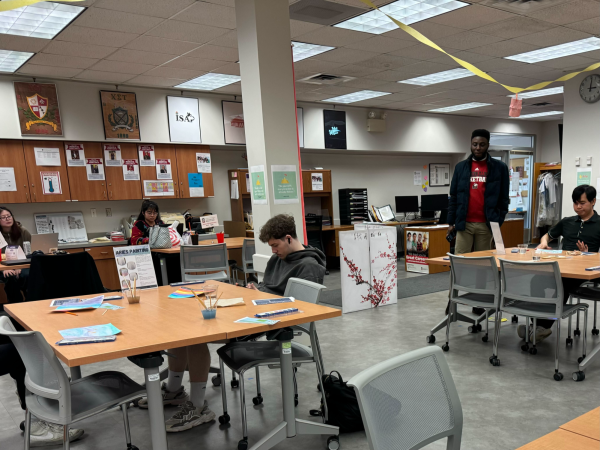

Panel discusses opioid epidemic

NIU Police commander Joseph Przybyla speaks at a STEM Cafe event Tuesday at Fatty’s Pub and Grill, 1312 W. Lincoln Highway, regarding the opioid epidemic impacting the community.

December 7, 2017

DeKALB — As the opioid epidemic tightens its grips on the surrounding area, a local pub hosted a STEM Cafe panel Tuesday to discuss how to combat its effect.

Students and residents packed into a back room at Fatty’s Pub and Grill, 1312 W. Lincoln Highway, prepared to have their questions about the epidemic answered by six experts: Cindy Graves, the Dekalb County Health Department Community Health and Prevention director; Joseph Pryzbala, NIU Police Department commander; Rick Amato, DeKalb County district attorney; Matthew Sprong, NIU assistant professor in the rehabilitation counseling program; Laura Meyer-Junco, University of Illinois, Chicago clinical assistant professor; and Steve Lekkas, DeKalb Police Department commander.

“The face of heroin is not your slimy, just-getting-out-of-jail druggies,” Graves said. “These are the boys and girls next door.”

In October, President Donald Trump declared opioid usage a public health emergency. In 2016, 64,000 Americans died of drug overdoses. Of these drug-related deaths, 66 percent were related to opioid usage, according to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

Despite the concern of the epidemic at the national level, the number of opioid-related deaths in the county have decreased from 27 in 2016 to 17 so far this year.

“This is something I always knew about,” said sophomore psychology major Paulina Ramirez. “But it didn’t hit me as something that happens a lot. DeKalb seems really quiet. This shocked me to hear.”

Graves attributed the reduction in fatalities to Narcan being more readily available, but she also admitted tracking Narcan use has not been as reliable as it should be.

Narcan is nasally administered and reaches the same neural receptors as opioids. The drug overrides the signals sent by heroin to bring a user out of an overdose, Graves said.

“The body is fighting back, so when these people pop back up from this, they can be violent,” Pryzbala said. “They get mad that you ruined their high.”

Pryzbala said NIU police officers are all cross-trained EMTs. During a 24-hour period, there is at least one patrol vehicle with all the same equipment as an ambulance; if an officer is called, there will always be narcan available.

But fear over being arrested and charged can prevent people from calling the police or paramedics when needed.

“People wipe the scene for fear of not getting in trouble,” said Lekkas.

Amato said there are programs for first time felony offenders to prevent them from being treated like prisoners once they are incarcerated.

“Often, our system has not looked at keeping them out of the system,” Amato said. “So we need our office to address those who have never been addicted to anything or never had prior court supervision to allow them to receive treatment.”

Lekkas said the problem with trying to provide these services for addicts to recover is the lack of room for addicts. When the nearly three-year state budget impasse ended, mental health and rehabilitation services lost a portion of their state funding.

“We have difficulty with a lack of funding,” Sprong said. “We used to have a six-month program, which anything less than 90 days is not as effective.”

Sprong said when the budget was cut, people were no longer being allowed six months of treatment in every case. In some situations, people who needed extended treatment were only provided service for two months.

Meyer-Junco is an academic pharmacist who monitors the use of prescription drugs in patients, and she said heroin is not the only opioid causing issues. Prescription drugs like Oxycontin, Vicodin and Oxycodone are being abused because people do not dispose of the pills after they are no longer needed.

About 80 percent of heroin addicts started with prescription opioids, according to the Illinois Department of Public Health.

“In 2012, doctors were prescribing enough opioids that every adult in America could have a bottle in their cabinet,” Meyer-Junco said.

The amount of leftover opioids creates a risk of being given away to family or friends who are in some sort of pain. Only 25 percent of opioids are attainted through a prescription, according to the CDC.

In 2014, the Food and Drug Administration put a stop to allowing refills of opioids like Vicodin, Oxycontin or Norco.

“This is a lot bigger than I thought it was,” said junior sociology major Elizabeth Houk. “I didn’t know that the leftover opioids were a problem at all.”

Lekkas said it’s important for residents to remember there are amnesty laws if they are concerned somebody may be at risk.

“There’s an amnesty law; if somebody is calling 911 to get help, they cannot be prosecuted for a minor violation of possession,” Lekkas said. “If it’s a circumstance when somebody might be using themselves and they think their friend is in the process of overdosing, there is no reason to hide it. The legislature built in the statute to protect these people. We just want to help.”