Last Day on Earth author comes to DeKalb for book signing

November 7, 2011

Author David Vann has investigated the life and death of Feb. 14, 2008 gunman Steven Kazmierczak more in-depth, perhaps, than anyone else. He will answer questions from the NIU and DeKalb community tonight.

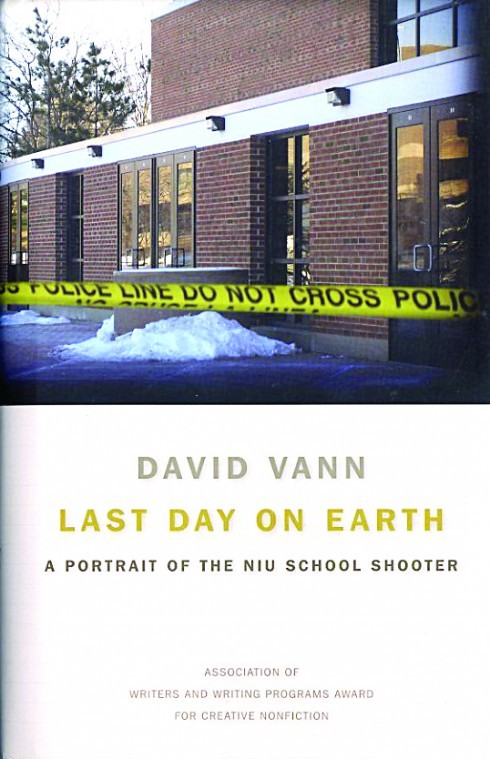

Barnes and Noble, 2439 Sycamore Road, advertises Vann’s appearance at 7 p.m. tonight as a reading and book signing of Last Day on Earth, Vann’s portrait of Kazmierczak released in October.

But Vann would like the event to be a question and answer session. Though he is reluctant to revisit a story he calls “ugly” and “grueling” to report and write, Vann said feels he owes it to the community to come to DeKalb.

“For two years [NIU Police] Chief [Donald] Grady wouldn’t release the report [about the shootings] and the info, and when he did release the report, it had lots of omissions and errors,” Van said. “It’s not a good report; it doesn’t tell you anything about the shooting. In fact, the federal report about the shooting just used my account, so my account is the only account of what happened. I feel that I owe it to the community to be there to answer questions, so I’d be happy to not read from the book and not give my own talk and just answer questions the whole time. I’d be happy to do any kind of format.”

Vann originally wrote an article about Kazmierczak on an assignment from Esquire in 2009, which was expanded into Last Day on Earth. The Northern Star spoke with Vann in October; additional questions never published from that interview appear here.

Northern Star: A lot of Last Day on Earth is excerpts from emails from Kazmierczak or interview with sources. Why did you give so much of the book over to these voices, not your own?

David Vann: I didn’t want it to be my opinions. I wanted it to be the record, the documents, so that when someone reads the book, they can have something like the experience I had in discovering the documents and doing the interviews and discovering the story, but can actually see all the information and draw their own conclusions from that information. To a huge degree, a reader of my book can do that without me getting in the way. There are these moments where I step in and say what I think, but they are very clearly marked; you can tell exactly when I am doing that. And all the rest is just fact. You get to read the emails, read his correspondence with his sister, find out what his mental health history was, so it’s a tremendous source of information in that way.

NS: You said you wrote the book in seven weeks so that it would be out of your life. Could you talk more about the difficulties in the process of reporting and writing the book?

DV: I think it’s important to get as close as possible to the truth, to try to understand everything and then, after that, I don’t want to spend any more time on it. And my objection to people in the area saying that they don’t want the story opened up again, they don’t want to the book, is that they haven’t had the full story. They need the full story once. After that, if they don’t want to ever hear about it again, then I’m totally with them on that. I understand. It really was grueling. I’m going to be rereading the book in the next few days before I tour around and I’m not looking forward to it. I’ve read it a bunch of times already, and I’d prefer not to read it again. But, anyone who’s affected by the story … it doesn’t make sense not to read it once, this blanket denial that “I don’t want to know anything about it.” We should want to know about he things that really affect and change our lives.

NS: You write very openly about your father’s suicide in the book, and you originally approached Kazmierczak’s story as a suicide rather than a mass murder. As a volunteer for the Ameican Foundation for Suicide Prevention, do you see suicide as a taboo subject in our society?

DV: Yeah, absolutely. I told everyone for three years that my father died of cancer because it was so shameful to say that it was a suicide. So I certainly experienced that first-hand. That’s also a big part of why some people in DeKalb don’t want my book to come out and don’t want the story to be out there: shame. But they could get past that if they realize that it’s not their shame, it’s America’s shame. It’s not the people in that community, in DeKalb, it’s what’s wrong with our society overall. And that’s one way that you can get past the shame of suicide – is to realize that there are 33,000 suicides every year in the U.S. It’s not one family’s problem. So I think that writing about it and talking about it is actually tremendously helpful for education and getting people to seek help when they need help, and I think that shame holds us back. Shame keeps us from dealing with problems … otherwise it just stays, it gains power through denial.

NS: Is there anything else you’d like to add?

Dv: I’d just [like to emphasize] that NIU was a good place for him, and that NIU improved his life. And that the people who knew him at NIU those people in the department where he first started grad school and as he finished undergrad … other teachers there and students … they actually couldn’t have seen warning signs. And so there’s nothing in my book that attacks NIU, and I wonder if people wonder sometimes if there is something there that is going to do that. And it’s not true. It really shows how he had this terrible history before. He had this huge drive toward improving and reshaping his life which happened at NIU, and then he went through a transition and regressed … and came back to erase everything that had been good about him. And that’s really the overall narrative.