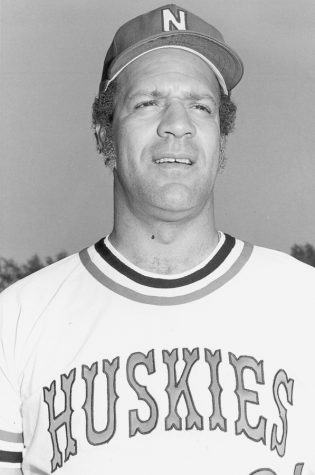

Remembering Walt Owens: Coach, teacher, mentor

September 24, 2020

Walt Owens, or “Coach O”, wore many hats in his 87 years of life before he died Sunday.

Owens played Negro League baseball under a pseudonym while also attending Western Michigan University. Owens was a high school teacher to Motown legends in Detroit. He was a baseball coach and faculty member for a combined 34 years at NIU.

Throughout his life, Owens was a mentor. His friend Larry Bolles, a former director of the Office of Community Standards & Student Conduct, can attest.

“No matter how difficult it could be, he always felt like he could turn it around,” Bolles said. “And he turned a lot of kids around. He always made the case ‘They need one more chance and they won’t ever be a problem again.’”

There are countless Coach O stories, and Bolles said he knows just about all of them.

Tickets would be left at roll call for ‘Coach O’ for concerts by The Supremes. The Temptations called him on stage one time in Chicago, and they joked about him talking Marvin Gaye out of playing football.

Owens got a call from Bud Selig, the commissioner of baseball, in 2008 when the MLB was set to hold a draft to honor Negro League players who never got to play in the Majors. Owens would end up being picked by the Chicago Cubs and earn a $5,000 yearly salary.

“He thought the guy was a crank call,” Bolles said. “I was sitting there listening and he looked like he was ready to hang up. Finally, the commissioner of baseball convinced Walt, ‘Yes, I am the real commissioner of Major League Baseball.”

Bolles’ favorite stories weren’t about Motown stars or Walt getting a check from the Cubs decades after his professional playing days. He said it was about Owens helping people that looked doomed to falter at NIU and how he put them back on track to a degree and better life.

“Wherever we’d go, people would come up and say ‘If I had never met Coach O, I’d never have graduated, or played in the Major Leagues, or make it out of high school,” Bolles said. “When I looked at Walt and we walked away and said ‘Larry, that feels good. We don’t get gold and we don’t get silver but doesn’t it feel good?’”

Whether as a coach or an educator, Owens life has been defined by the ways in which he helps nurture the academic career, athletic career and overall life of students at NIU.

Days in Detroit and summers among the Stars

Owens might have been born in Cleveland, Ohio, but his story couldn’t start anywhere but Detroit, Michigan. In high school, Owens won three city championships in baseball and earned a scholarship to play baseball and run track at Western Michigan University.

During the summers off from classes, Owens did what most kids did and picked up a summer gig. His happened to be playing for the Detroit Stars of the Negro Leagues.

Owens played three summers of professional baseball and would go against the likes of Satchel Paige and “Double Duty” Ted Radcliffe in between semesters at WMU. Owens ultimately stopped playing with the Stars when he was convinced to stay in school by eventual National Baseball Hall of Famer and Stars legend Norman Stearns.

To retain his amatuer status, Owens played under a variety of fake name and effectively made whatever he would accomplish in the Negro Leagues a virtual mystery. He used the names of guys he played with in high school — Bernie Porter, Eddie Williams, Moses Willis — and fooled even those he’d eventually work with like Mike Korcek, former NIU Sports Information Director.

“It’s funny, I found an old media guide where I wrote his bio when he was an assistant,” Korcek said. “There’s nothing about him playing in the Negro Leagues. I’m embarrassed but he never talked about it.”

Owens legacy in Detroit sports wouldn’t end with his time in the Negro Leagues. He broke the color barrier for the city in baseball when he joined the all-white Pepsi-Cola team in 1957, a year before the Detroit Tigers were first integrated.

“He and I took a trip to Kansas City where the Negro League Hall of Fame is located,” Bolles said. “When we go there we saw some other people who played in the Negro Leagues. Walt was spoken very highly of by those players. They thought he had very good skills.”

After graduating from WMU, Owens turned down an opportunity to go back to the Negro Leagues and opted to become a high school teacher and a coach back in his hometown of Detroit.

Owens would teach some of the young stars of the growing Detroit music scene of Motown, including members of The Supremes, The Temptations and Mary Wells. When he became a baseball coach, he helped mentor players to accomplishing the dream he never could of reaching the major leagues. Players like Alex Johnson and Willie Horton would win city baseball titles under Owens in high school and go on to become All-Stars.

“The kids loved him and he loved the relationships he built by teaching teenagers,” Bolles said.

Bolles said seeing a display of city championships trophies and other accomplishments put into perspective how much Detroit meant to Owens.

“He got so many awards from the city of Detroit for athletics and things he did,” Bolles said. “I went in his basement one time where he had all those awards and I said ‘Walt, you loved Detroit but they loved you back.’”

How an assistant coaching job turned into 34 years at NIU

When Emory Luck took over the NIU men’s basketball program in 1973, he turned to his home state of Michigan and picked Owens to be his assistant coach.

Owens was distant from Detroit for the first time in a long time, but by the time his career at NIU had ended, he’d spend more of his life in DeKalb than the Motor City.

After three years with the men’s basketball program, Owens took over as the head coach of the baseball team. In seven seasons, Owens won 137 games in what still stands as the third most wins by a manager in program history.

Owens’ time with the program, and ultimately in coaching, came to an end when the program was cut in 1982. Korcek said Owens stood behind his players and fought to keep the program alive.

“I think every coach fights for their program,” Korcek said. “Walt did his best and fought for his program.”

Even with his coaching career cut short, the legacy and impression he’s left on the program is still felt today. In February, NIU’s athletic department announced renovation plans to the baseball field and facilities, including renaming the field “Ralph McKinzie Stadium at Walt and Janice Owens Park.”

“The best way I could describe Coach O and what he means to Huskies baseball is he’s probably the leading face on the Mount Rushmore of NIU baseball,” NIU baseball Head Coach Mike Kunigonis said.

Owens, who originally thought he wasn’t long for DeKalb, stuck around for only about another quarter century as a faculty member that taught everything from coaching classes to physical education to communications.

The roles changed, and sports for Owens were kept mainly to the recreational softball he played throughout his time as a teacher. But Korcek said he treated the students he taught the same as those he coached.

“In those years, just like he was in Athletics, Walt would mentor the students,” Korcek said. “‘Hey, do your thing. Get this stuff done in the classroom.’ That to me was really impressive.”

The work Owens made on campus didn’t end in the classrooms either. During his time at NIU, he served on the Presidential Commission on the Status of Minorities and the Task Force on Racial Discrimination and Sexual Harassment.

Owens even served as a board member on the National Congress of Black Faculty in Washington D.C. and on the Illinois Committee on Black Concerns in Higher Education.

“He’s a man of substance,” Korcek said. “Walt represented himself, Northern, black faculty and the staff on these committees. He was involved with everybody and represented them well.”

In 2007, Owens suffered a stroke, recovered, and decided to retire. When the Daily Chronicle and reporter Bobby Narang interviewed Owens about his retirement, he talked about his retirement party and finally seeing just how many people he impacted.

“At my retirement, people were flying in from Florida, Tennessee and other places. I didn’t even tell the people in Detroit,” Owens said in a 2007 Daily Chronicle article. “I cried at my retirement party. I couldn’t stop. Since the 12th grade I’ve always had a handkerchief with me every day. Sometimes even two. But I didn’t have one at the retirement party. But to feel the love. I knew people liked me, but I didn’t know the love was so deep.”

A legacy that lasts on many levels

The weight of Coach O’s legacy is felt heavy on anyone who will talk about him. Even though he only knew Owens for a short time, Kunigonis said he understood the influence Owens had on NIU sports and so many of its students.

“Sports were a big part of his life, but it wasn’t his entire life,” Kunigonis said. “His family and mentoring young people meant a lot to him. He touched so many young lives.”

Korcek said he understood how much the mentorship of someone like Owens could mean, himself saying former Northern Star advisor Roy Cambell played a huge role in his college life.

“[Owens] is already in the NIU Athletics Hall of Fame but I think he should be in the mentorship hall of fame,” Korcek said. “I think that’s very important. When you’re a college kid, you need someone who cares for you and cares about you.”

Bolles said he knew virtually every side of Owens. Bolles knew the mentor and the coach and the teacher, but he most importantly knew Owens as one of his best friends.

“Walt was a good friend,” Bolles said. “Now what is a good friend? I think a good friend is someone who always sees the best in you, even on days you don’t see it. He’d tell you the truth about what he sees in you.”

The people who only saw Owens’ resume could probably debate endlessly about what part of his life will have an everlasting effect on the world he made better in the 87 years he was on it.

What did Owens himself see as the most important role he played in his life? He got the most kick out of helping others.

“I used to think I could save everybody,” Owens said in a 2007 Daily Chronicle article. “You see people do things with their lives that are just unbelievable. That’s the part I’ll miss.”

In 2000, Owens was inducted into the Negro League Baseball Hall of Fame. In the years after his 2007 retirement, Owens was inducted into the NIU Athletics Hall of Fame, was given the E.B. Henderson Award by the National Association for Health & Fitness, and honored by the Detroit Tigers for the 100th anniversary of the Detroit Stars.

For Owens, it was never about the gold and silver. It was seeing people make the most of their lives that made him feel good.

Owens is survived by his wife Jan and his four children.