Alumnus details 2013 death of Terrance Franklin in new book

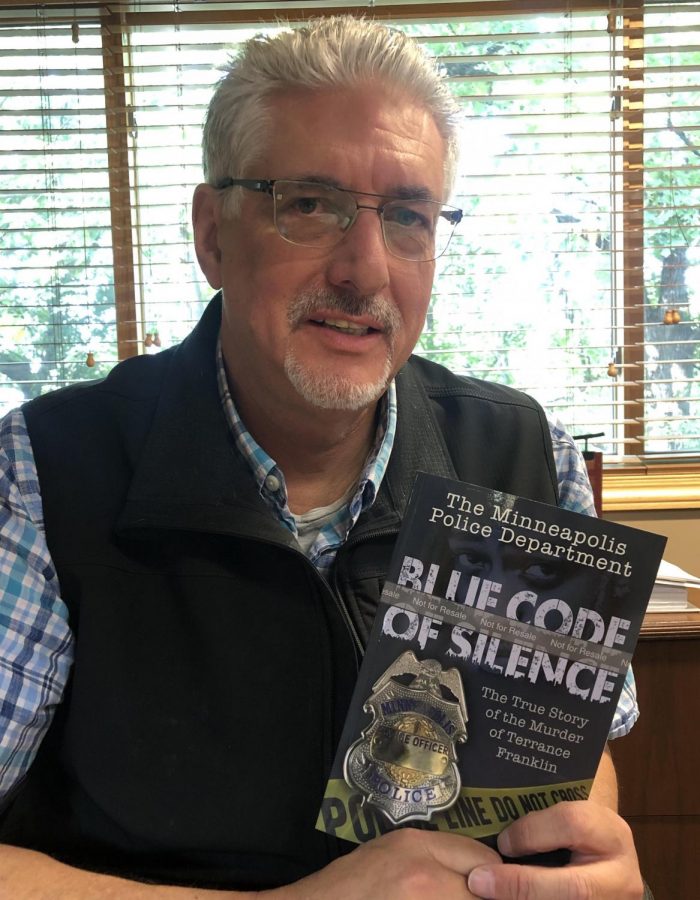

Courtesy of Mike Padden

Author Mike Padden holding his book “The Minneapolis Police Department: Blue Code of Silence”

September 25, 2020

George Floyd, a 46-year-old Black man, died May 25 after a Minneapolis police officer placed his knee on Floyd’s neck while apprehending him until Floyd couldn’t breathe. Floyd’s death motivated Mike Padden, NIU alumnus and civil rights attorney, to write a book on a lawsuit he finished representing just two months before Floyd’s death: the case of Terrance Franklin, a Black man age 22, also from Minneapolis.

After almost seven years of representing Franklin’s case, and nearly five since Franklin’s family filed a wrongful death lawsuit, the Minneapolis City Council approved a $795,000 settlement.

The officers involved were not charged criminally and were not disciplined by the department.

The final day of court lasted seven hours, and Franklin’s dad, Padden’s client, was the only one there from the family. Although he did not receive the full amount, he was pleased with the resolution, and that was fine with Padden, he said. Franklin’s father was very emotional when his son finally received justice after nearly seven years without him. The Minneapolis police chief was at court, and he consoled Franklin’s father, Padden said.

“This had gone on for so long, and we finally had closure,” Padden said.

“The Minneapolis Police Department: Blue Code of Silence” delves into the truth of the Minneapolis Police Department and The Blue Code of Silence in law enforcement, and how it played a role in Franklin’s case, Padden said. His first self-published book, written over the course of three months, can be found on shelves Oct. 5.

On May 10, 2013, Franklin was visiting a woman at an apartment complex in Minneapolis. A janitor who worked at the complex called the police and claimed Franklin resembled someone he thought was responsible for a burglary in the apartment complex that took place 10 days prior, Padden said.

Police arrived in the parking lot, and an officer approached Franklin’s car door with a gun drawn. Franklin drove away. There was no allegation that he just committed a crime, only the allegation that he had done something 10 days before, Padden said.

Franklin drove a few blocks, stopped and got out of the car and fled on foot. He was eventually found by the police inside his home, where he was killed in the basement.

Five officers — Ricardo Muro, Andy Stender, Mark Durand, Lucas Peterson and Michael Meath — were in the basement with Franklin. Police said Franklin grabbed one of their guns and wounded officers Muro and Meath. Officers Peterson and Meath shot and killed Franklin, according to the case complaint.

The big question, Padden said, was did the police officers kill him for good reason or was he wrongfully killed? He said his contention was that Franklin was wrongfully killed.

The shooting occurred several years before Minneapolis police officers were required to wear body cameras, Padden said.

The primary reason Padden and his team were able to prove it was wrongful death, however, with help from video evidence that a citizen across the street from Franklin’s home took on an iPod touch. Padden said the man who recorded picked up audio coming from Franklin’s basement.

Because of that video, Padden was able to prove that Franklin was actually arrested by the police. The time period from when the gun went off, injuring two officers, to the time Franklin was killed was over 70 seconds. Padden and his client, Franklin’s father, claimed the police department made up their story, and that the gun went off due to a firearm phenomenon known as “accidental discharge,” and that’s how the officers were injured, he said.

Padden said MPD wrongfully killed Franklin partially due to retribution to the arrest and also the notion that Franklin tried to run over and kill a police officer, which was not true at all. There was a video to prove it, Padden said, but an officer communicated it over the radio.

Padden said he found that the police department had engaged in a coverup with the evidence provided. The blue code of silence is when police officers avoid reporting crimes and misconduct by their colleague. Padden believes it played a part in this case.

“We feel strongly that [Franklin’s] race had a lot to do with his death,” Padden said. Officer Peterson called Franklin the N-word twice, according to the complaint.

The Minneapolis Police Department is an agency that’s had this problem for many, many years, Padden said. As he mentions in the book, the federal government investigated the department. In 2015, the government told the Minneapolis Police Department that things need to change before it’s too late, he said.

Michael Kosner, Chicago co-trial counsel for Padden, thinks some of what we see unravelling in the world today is a direct result of how low the bar has been set for who gets to be a police officer.

“There [are] a lot of people that, from a personality perspective, from an intelligence perspective, absolutely, positively have not earned the right and the privilege to be law enforcement,” Kosner said.

However, this book is not anti-police, nor is it intended to convince readers that this was a wrongful death, although Padden defended that argument and believes that. He said he sees his first book as a mystery-suspense book rather than a true crime book.

Padden said in addition to Franklin’s case he also discusses other civil rights cases that were happening outside of Minnesota that impacted the way people perceived law enforcement throughout the book, like the Laquan McDonald case in Chicago.

Padden wants readers to be more careful about what large organizations tell them regarding an unusual situation after reading the book.

“You need to scrutinize, see if it passes the smell test, have an antenna up to see if a cover-up is involved,” he said.

The bar for law enforcement has to be much much higher than what it’s previously been set at, Kosner said.

“Once that occurs, we’ll start to see a drastic reduction in some of the unjustifiable brutality that has been taking place across the country for the last 150 years,” Kosner said.