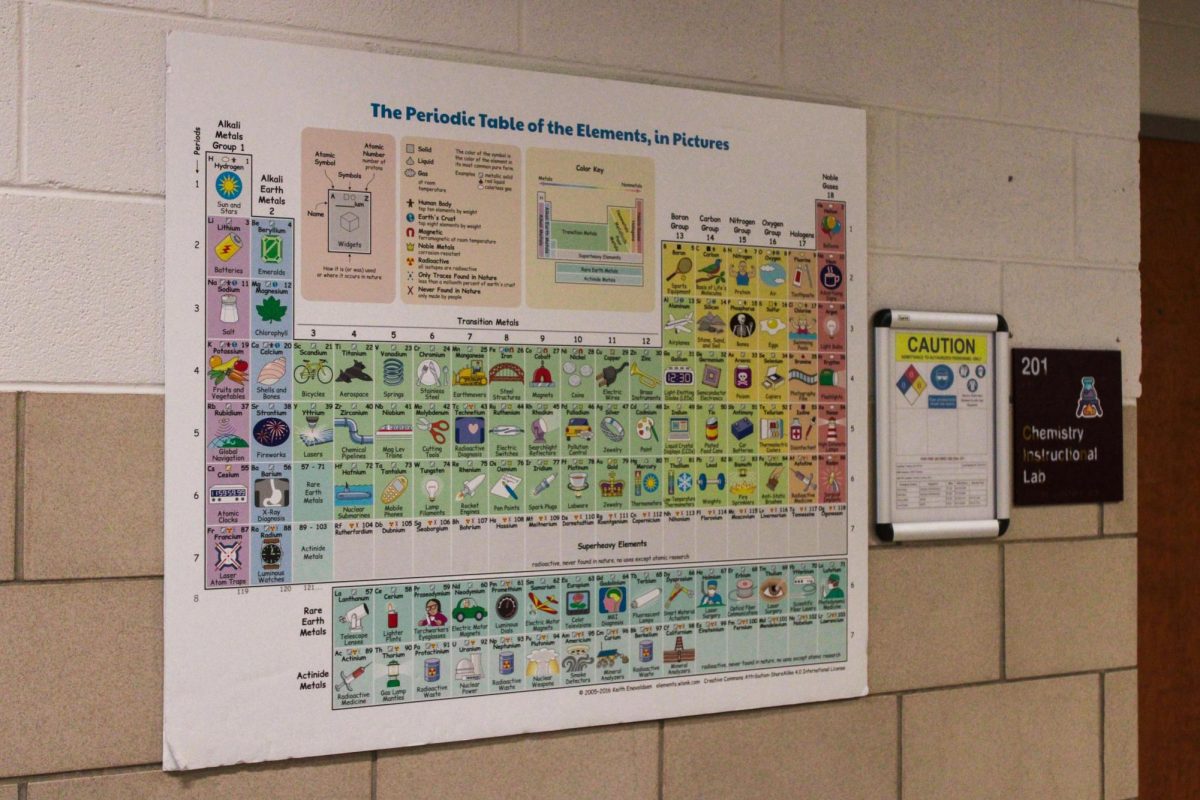

Observe, hypothesize, experiment, repeat. It’s paramount that each blossoming scientist learns how to use the scientific method, and uses it well, but there’s also valuable lessons for non-scientists hidden in this special way.

I: OBSERVE – STAY CURIOUS

The scientific method starts with noticing something, and with thinking: I wonder?

Scientist or not, the world is your oyster, your box of chocolates, your baobab tree, your perfect compass. There is so much to look at, to smell, to hear, to taste, to feel and sense it, you should.

II: FORM A HYPOTHESIS – DON’T FEAR FAILURE

In grade school, we practiced developing this “educated guess” over beakers of baking soda and vinegar. For scientists, the hypothesis sets the boundaries for each research journey.

Perhaps the “educated” part is what modern leaders could learn most from, but for those of us who need the boost, this step also encourages self-confidence. Putting yourself out there and claiming “this is what I think!” at the risk of being wrong is not easy.

It’s far easier said than accepted, but failure isn’t your enemy.

III. TEST THE HYPOTHESIS – STEP OUT OF YOUR COMFORT ZONE

For scientists, this step tests the hypothesis – but also the scope of the scientific mind. In a quality experiment, every variable must be accounted for.

What might unwittingly affect the experiment? What must be controlled? What materials are required? How should they be prepared?

It’s hard work – just like college – but you’re no stranger to that.

IV: START AGAIN – BE HUMBLE

It is not the goal of the scientist to prove anything. In fact, the goal of the scientist is to continue working to prove themselves wrong, explained Mark Frank, the chair of NIU’s Earth, Atmosphere and Environment department and a professor of EAE.

“The challenge is, you can never prove that said hypothesis, so you end up saying, ‘Okay, I didn’t disprove it. Let me try another test. Let me try another test, let me try another test,’ right?” Frank said. “And ultimately, if you can continue to actually come up with different tests, different ways, or collecting more and more data, ultimately you can say, ‘well, this hypothesis still stands,’ and that’s about the best that you can do.”

The understanding that we are not divine enough creatures to truly prove anything without a shred of doubt is what makes science reliable and what keeps its methods so clean.

“We don’t prove things in science,” Frank said. “You may have a hypothesis that you’re working on, and you may have data, but you have to always be willing to look at the fact that other people’s data may show that you are wrong, or that you get new data that show that you’re wrong. That’s where you have to be willing to disprove, you have to have an open mind that other people may know things you don’t know, and that they have found a new way to think about something.”

Science must be a balanced mix of confidence and humility: Of being sure of your opinion and being willing to change it. So should everyday life.

For nonscientists, humility keeps us appreciative and curious, and happier because of that.

If we knew everything anyway, wouldn’t life be boring? What mysteries would we have to pursue? Magic exists clearly when you can accept the unknown; if you already know everything there is to understand – or think you do – it vanishes from sight.