Editor’s note: Digital Managing Editor Joey Trella was born bilaterally deaf. She received her left cochlear implant at 1-year-old and her right side at 5-years-old.

Being stuck between two worlds is no easy feat, especially when it is part of your identity. The Deaf community has been known to be inclusive to those who are curious about their community – except those with cochlear implants. The Deaf community cannot claim to be inclusive unless they accept all forms of deafness or hard of hearing.

The Deaf community is accepting of hearing aids but not of cochlear implants which shows preference. No matter how you look at it, hearing aids and cochlear implants do the same thing, help those in the deaf community.

There is nothing wrong with using any type of device for disability support. It’s time for the Deaf community to update its idea of inclusiveness to modern day.

The capital “D” in the term “Deaf community” has a meaning behind it. It involves four defining dimensions, according to Coordinator of Deaf Studies and American Sign Language Instructor Taylor Hartman, who is also deaf.

“There is political, audiological, social and linguistics,” Hartman said. “Political means you’re advocating for the rights of deaf people, like the laws or trying to help improve the community and make things better for the community, improve the community. Audiological would be a person that must have some form of hearing loss. It doesn’t matter if it’s mild or profound, but there has to be some hearing loss. Social, you want to go to Deaf events or hang out with people who are deaf. And then linguistic means they know ASL. It doesn’t matter if you learned finger spell or basic signs or advanced signs, but you have to try to learn the language of ASL.”

Lowercase “d” deaf is for those who have some form of hearing loss but do not fit all four dimensions of the Deaf community. Those with cochlear implants are a part of the community even if they aren’t involved with other dimensions of “Deaf.”

To even have dedicated definitions to create two different communities of deaf people makes deafness seem like it’s two different disabilities. The only way community members should differentiate themselves is their level of hearing medicially, not how they associate themselves with the word “deaf.”

“I’ve never really identified with any community. I wasn’t really aware what the ‘Big D Deaf’ meant until I was much older,” said Zayna Nasser, a junior majoring in communicative disorders. “I don’t really like the labels because they try to fit you into one box when I don’t feel like I am part of any singular one. I identify as a deaf person, and I’m proud of it, but I also identify as a hearing person too. I feel like I am on the fence between both worlds.”

Nasser was born bilaterally deaf. By the time she turned 15 months old, she received her first cochlear implant on her right side and a year later, she got her left side implanted.

These required dimensions that create the Deaf community have failed to be inclusive. Inclusive means including everyone, especially being open to those who have been historically excluded due to their race, gender, sexuality or ability, according to Merriam-Webster.

Historically, deaf people with cochlear implants have been wrongfully excluded from the Deaf community.

Growing up, Nasser went to an early intervention school for Deaf and Hard of Hearing called “Child’s Voice” for five years then went mainstream to public schools. She wasn’t taught ASL.

“They wanted to teach us how to speak and not rely on signing,” Nasser said. “So I never used sign growing up; but when I got to college, I wanted to learn, so now my minor is Deaf studies, and I’m learning ASL.”

The separation between the Deaf community and those with cochlear implants might be understandable to some, but it’s not a strong enough reason to exclude people who are still technically deaf.

Deaf people find it hard to accept those with cochlear implants because they might not conform to the old ways of the Deaf community. But nonetheless, deaf people with cochlear implants are still deaf and still deserve to be a part of their community.

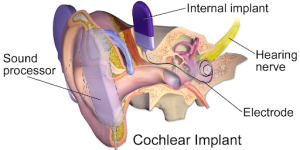

When cochlear implants were first approved for adults in 1985 and children in 1990, the Deaf community has been outspoken about the implants being a threat to their community.

“As recently as the 1990s, many Deaf people rejected the idea of cochlear implants and either shunned or threatened to shun any Deaf person who dared to have one,” wrote Tom Humphries and Jacqueline Humphries in their article published in 2010 in The Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education.

The 2010 article explained the tension between those with cochlear implants and the Deaf community is not against the devices itself. The Deaf community was also frustrated with: doctors advising parents to have their children implanted and not rely on ASL; parents deciding for their child whether to have an implant; and the threat of the Deaf community being eradicated or “fixed,” either via eliminating their deafness or eliminating their language.

“I think they placed their anger on the medical field and doctors because the doctors either weren’t aware of the resources the community could provide,” Hartman said. “Also, there were a lot of anger at parents for putting a cochlear implant in their children.”

Hartman’s mom learned he was deaf when he was 2 years old, but they still don’t know if he was born deaf. He was given the opportunity to consider cochlear implants when he was young but was on the fence. Hartman ultimately decided against it and has a hearing aid for when he teaches.

“I understand that the divide is slowly changing, and it’s improving because more people have become aware that many people who have a CI (cochlear implant) – they get CIs when they’re young – and they don’t have a choice whether they get one or not,” Hartman said.

But the Deaf community shouldn’t shame parents for making a decision for their child when they’re young or those who eventually get a cochlear implant when they’re older. Parents are making a decision about what they feel is best for their child, not what’s best for the community.

According to the Boston Children’s Hospital, doctors recommend cochlear activation 3 years or younger to learn sound while developing language skills.

Advantages of early implantation showed that those implanted at 9 months had a similar Functional Listening Index – which tracks a child’s listening skill from birth to 6 years old – to normal hearing, according to a 2022 study published in the National Library of Medicine.

“I wouldn’t change a thing because if this is what my parents chose for me, and it was right for me, and I feel successful now because of it,” Nasser said. “I see it (cochlear implant) as a tool, not a permanent fix because, at any point in my life, I can take it off and be deaf again.”

While the Deaf community is an important one, let’s stay true to our word about being inclusive and adjust to the modern era of Deaf community. We must recognize both those with or without some sort of aid.