In recent weeks, one of the bloodiest conflicts of the 21st century has rekindled. The Democratic Republic of the Congo – not to be confused with the Republic of the Congo – has fallen into a new spiral of violence which has resulted from a conflict in a cryogenic state that has now emerged from sleep, threatening peace and prosperity in Central Africa and the lives of millions of people.

Even when, at first sight, it might seem that very little of this conflict could affect us and concern us, the role that the world and especially the most industrialized countries play is much bigger than suspected.

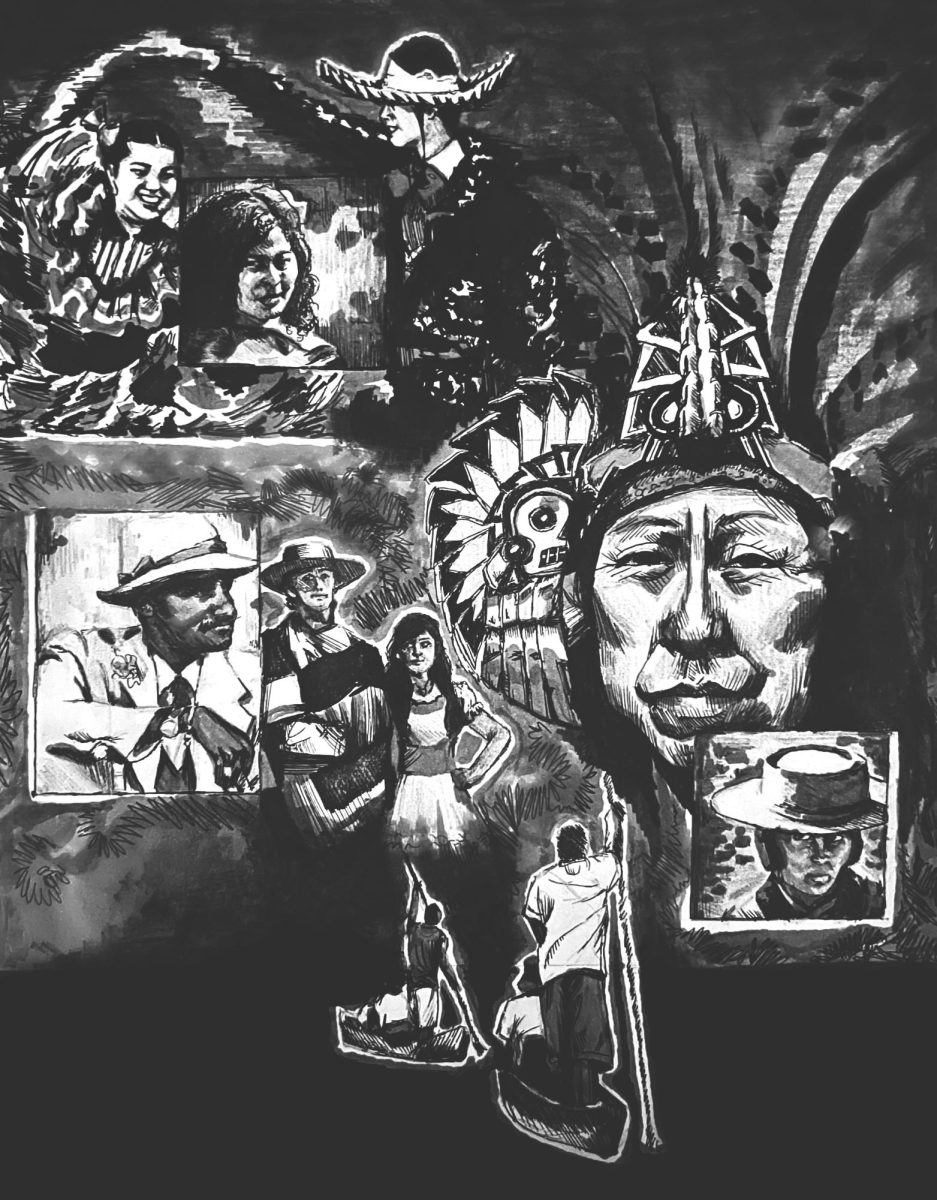

“How do we understand this conflict? We cannot understand the conflict without really understanding the, you know, the long, complex history of the Congo, and I say long, long as it connected to the role of the natural resources” – says Ismael Montana, professor of History at NIU- That is why the second question has to do with colonization, advent of colonization in relation to the natural resources in that region, and then post-colonization.”

This conflict has its origins rooted in the colonial history of the Congo, under Belgian mandate. The unusual violence with which Belgium exercised their mandate over the Congo 8 to 10 million dead and a few million more maimed – led to the Congo gaining its independence from Belgium in 1960.

“There was an outcry because of abused, humanitarian abuse of the people who were working on these areas (extraction of rubber),” said Ismael Montana, a history professor. “And the result of that outcry was that Congo was transferred to the Belgian state. Thereafter, the Belgian State became administer of what became known to the Congo. But in terms of brutality, nothing really changes.”

Unfortunately, at the time of a peaceful transition of power, there were no educated people in Congo who had the knowledge of economics or politics for the new government, which led to a great political destabilization, which in turn led to several conflicts. The best known are the coup d’état of Joseph-Désiré Mobutu in 1965, the first civil war in the Congo and the conflict in Katanga.

The Congo was not the only Belgian colony in Africa. Right next to it are two small nations, Burundi and Rwanda. Like the Congo, Rwanda also has a turbulent history, marked by civil wars and conflicts between the two ethnicities present, the Tutsis and the Hutus. After the assassination of the prime minister in 1994, the Rwandan genocide began.

Almost one million Tutsis were killed in 100 days. Contrary to popular belief, however, the genocide was also political in nature, since some moderate Hutus were also killed by more radical Hutus.

The Rwandan genocide and subsequent civil conflict led to a mass emigration of Tutsis to other countries, especially to Uganda, because Mobutu, while in power in the DRC, supported the Hutus in their slaughter against the Tutsis.

In Uganda, one such tutsi immigrant named Paul Kagame, who previously fought in the Ugandan civil war, assembled an army together with another Rwandan named Fred Rygeema and formed the Rwandan Patriotic Front.

The Rwandan civil war began in 1990, but did not end until 1994 when Kagame took advantage of the Hutu coup d’état generated by the assassination of the Rwandan president and the prime minister and launched an offensive against the Hutu militias which was more focused on genocide than defending the interim government.

The surviving Hutus who participated in the massacre fled to the border province of Kivu, Zaire (DRC) and started a guerrilla war against the Kagame government. In response, in 1997, Rwanda, Burundi and Uganda together with a political coalition of opposition to Mobutu launched an offensive against all Hutu operating bases in the DRC, starting the first war in the Congo.

The war ended with the overthrow of Mobutu in favour of Laurent Desire-Kabila. The latter, however, was unwilling to act as a puppet for its former neighbouring allies, expelling the Rwandan advisers from the Congo. Rwanda and Uganda decided to overthrow the Congolese president again, forming a new insurgent group for it, called the Rally for Congolese Democracy.

But this time, it would no longer be a conflict in the Congo. On the side of Kabila, Angola, Zimbabwe and Namibia sent troops, in addition to having the support of Chad, Libya, Sudan and about a dozen militias that for external reasons had more affinity with the Congo.

On the side of Kagame, Uganda, Burundi and Rwanda joined forces again, but this time they included another dozen guerrilla groups and insurgents in the Congo and their allied countries, even opposition parties like UNITA in Angola provided support.

The situation seemed to be at a stalemate until February, when troops from the insurgent movement on March 23 launched a strong offensive in the east of the country and took Goma, supported by the Rwandan government of Kagame, who is now a lifetime dictator of Rwanda, which de facto makes the war a conflict between DRC and Rwanda.

This conflict (not just the Second Congo War, but the whole conflict) is by far the bloodiest, not only of the 21st century, but also since WWII, overcoming more known wars such as the Yugoslav wars of the 90s, the Russian-Ukrainian War of 2022 and most recently the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict.

But why should we be interested in this conflict? DRC holds 55% and 80% of the world’s known reserves of cobalt and coltan respectively. These two minerals are important for the world’s economy, since tantalum is obtained from coltan.

Tantalum is a mineral used in the production of all electrical products such as mobile phones, tablets, consoles, computers and anything that contains a microchip. Cobalt, on the other hand, is used in the construction of superalloys for aircraft engines, nuclear reactors and other types of mega constructions.

This often leads the militias to focus their efforts on controlling some of these mines, enslaving the adjacent population to extract the mineral and sell it to Rwanda and Burundi, who distribute it internationally. In other words, that iPhone you bought last month, the new laptop you have had since the beginning of the semester, among other things, helped finance the deadliest conflict of our time.

For the time being, the only thing that could help reduce serious escalation is to secure mines from insurgent groups and warlords and to impose international sanctions on Rwanda to reduce the country’s benefits from the war in the Congo, as well as to reduce its aid to the M-23.

But what about the help of ordinary people like university students? Realistically there is nothing that can be brought to this conflict, because we have no control over our demand for coltan, as it’s something we consume indirectly.

But it is important to know some of your money goes into the pockets of insurgent groups in the Congo. There are many products we consume daily and do not know where they come from or who is affected by the power to acquire them.

The lesson that the Congo leaves us is not only the immense fortune we have to be in America rather than the countries or regions in constant war, but also to remember the position of privilege we hold normally carries with it a responsibility to look after or affect in one way or another the rest of the world’s disadvantaged nations.

There are two great ways in which we can affect the conflict – through what we consume and who we vote for.