Pierce remembers time playing in different states, overseas

December 5, 2019

DeKALB — Not many people can say they’ve lived in five states and three countries by the time they were 18 years old. Even fewer can say they played hockey while doing so.

Hunter Pierce was born in North Pole, Alaska. When Hunter was eight years old, his dad, Russell Pierce, decided to become a doctor. Russell made this decision at a late age, so he wanted to fast-track his schooling. This meant taking any opportunity he could to advance his career, which resulted in the Pierce family constantly moving.

The first stop was the Caribbean for one year when Hunter was about nine years old. Then, it was England for a year, followed by Arizona for another year. After that, it was Wyoming for two years. Then, once Russell was officially a doctor, the family settled in Fairbanks, Alaska when Hunter was 14 years old. They’ve lived there ever since.

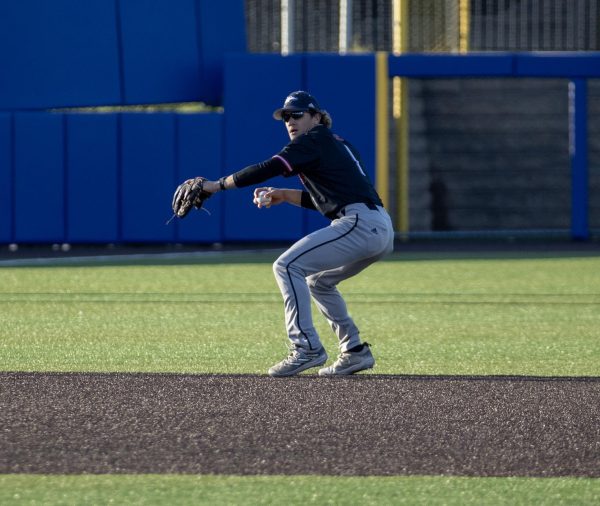

However, Hunter didn’t stay in Fairbanks long. After graduating high school, he played junior hockey in Montana for the Helena Bighorns for two seasons. Now, he’s a first-year forward for NIU’s Division 1 team.

Hunter was only two years old when he started playing hockey. He said he was practically born on skates. Growing up, Hunter’s older brother John Pierce also played hockey and would always beat Hunter when they faced off. Eventually, the tides turned and Hunter started winning the matchups. Even then, John found a way to make it enjoyable for himself.

“He has that big-brother thing where he knows what I’m going to do, [and] how to get in my head,” Hunter said. “He can’t beat me physically or on my edge work, but he’ll [mess] with me, then it’s over.”

Throughout all the moving the 20-year-old did growing up, hockey was one of the constants in Hunter’s life. He also noticed the differences in the way the game is played in each location he lived.

Hunter and John tried making the best of their time while living in Saint Martin, a small island country in the Caribbean roughly 230 miles east of Puerto Rico. While living on the island, the lack of hockey made it Hunter’s least favorite place to live.

“Just me and my brother played ball hockey because nobody else knew what hockey was,” Hunter said. “It was really weird because most people would probably like the Caribbean, but I didn’t because there was no hockey. It was sort of bummy.”

The Pierce brothers also played flag football, soccer and tennis to stay in shape for their eventual return to the ice.

In England, there wasn’t much physicality in hockey. There was more finesse and passing. Hunter also had to adjust to international rinks, which are 15-feet wider than rinks in North America. The Huskie said he prefers North American rinks because there’s less space, which raises the intensity of the game.

In Arizona, the coaches focused on scoring, and there wasn’t much attention given to defense. Hunter and his team just tried putting up as many points as possible. He said it was a run-and-gun style of play.

In Montana, it was all about playing with grit and winning by any means necessary. This was Hunter’s favorite place to play, because he said he likes playing with finesse, and he loves the feeling of evading a defender trying to hit him.

“The league in Montana was super grimy and all about fundamentals and hitting,” Hunter said. “We hated the other team, and they hated us, and it was going to be a bloodbath to see who won.”

While playing in Montana, Hunter checked ‘getting in a hockey fight’ off his bucket list, though he wasn’t very pleased with his performance.

“I’m a lightweight, so I picked another lightweight,” Hunter said. “It was a soft fight. It was just something I had to do. I played junior hockey for two years and knew I had to fight someone.”

Similar to hockey in Montana, Alaskan hockey has a rugged edge to it. If you don’t keep your head up, you’re going to get checked, Hunter said. Passing is also a key part of the game.

Playing for NIU, the 5-foot-9-inch forward said he noticed college hockey games have fluidity and are pass-oriented.

He’s also noticed players getting anxious with the puck, causing them to make snap-decisions when it isn’t always necessary.

“There’s a lot more time and space than [players] think [they] have,” Hunter said. “People don’t come in to crush your day, they’re going to just try taking the puck away.”

Hunter said the way hockey is played is one of many things that make Alaska unique.

His hometown of Fairbanks is Alaska’s third largest city, with a population of 31,516. Hunter says back home, there are usually two distinct types of people.

“There [are] yee-yee and granola, and you vary on that scale,” Hunter said. “It’s either, ‘let’s go to the farmers market and find natural produce,’ or it’s ‘I’m going to put this stuff on my truck to make it brighter and shinier.’”

Hunter said that while he does enjoy nature, he wouldn’t categorize himself as ‘granola,’ but he can’t say the same for his family. They have chickens, a garden and even a greenhouse.

They eat a lot of healthy food, like quinoa and salmon, which they catch and clean themselves. So, when Hunter got on campus, he was excited to try the dining halls.

“I eat cookies, chicken strips and all that because I’m super about it,” Hunter said. “The food [at the dining halls] is repetitive, and it’s not the best stuff, but it’s way better than salmon and rice everyday.”

While Hunter enjoys the dining hall food, the rest of DeKalb leaves a lot to be desired. When back home, he loves being out in nature and going for hikes, floating down a river or even mudding. In DeKalb, there’s just a lot of flat, open land.

“There’s nothing here besides corn, and it’s not great to look at,” Hunter said. “I’ve tried doing “naturey” stuff here, but it’s just not the same; it’s not even scary. You go out in Alaska and lose cell service. You’re out there. Here, it’s just nothing. It’s like, ‘Oh yeah, I’m in a couple trees right now.’ That’s about it.”

Hunter also wishes the people at NIU were more active. He can always count on his fellow Alaskan teammate, first-year forward Rodahn Evans, to get out and be active with him.

“In Alaska, people are always wanting to do stuff,” Hunter said. “[Evans] is a full-sender; he’ll do anything you ask him. I was trying to get people here to go to Chicago, and they were like, ‘Oh, I got family in town’. People here go back to visit their family so much. I haven’t seen my family in three months, and I’m completely OK with that. I’ll give them a call; it’s chill.”

Hunter said he has also heard his fair share of misconceptions about Alaska.

People have told him it’s cold year-round and never warms up. They ask if he lives in an igloo and if he skis to get from place-to-place. The most notable misconception is about Alaska’s geographic location.

“The biggest one is that it’s by Hawaii, and it’s not actually connected; it’s an island,” Hunter said. “That one’s the best. You can mess with those people, because they obviously aren’t too intelligent.”