Knee injuries jeopardized Neslund’s career, the Huskie fought back for her final season at NIU

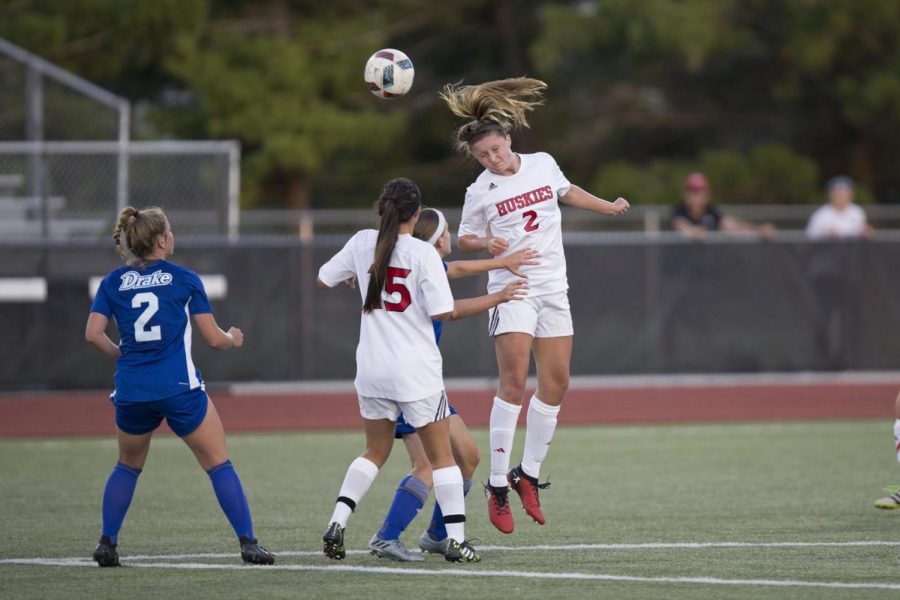

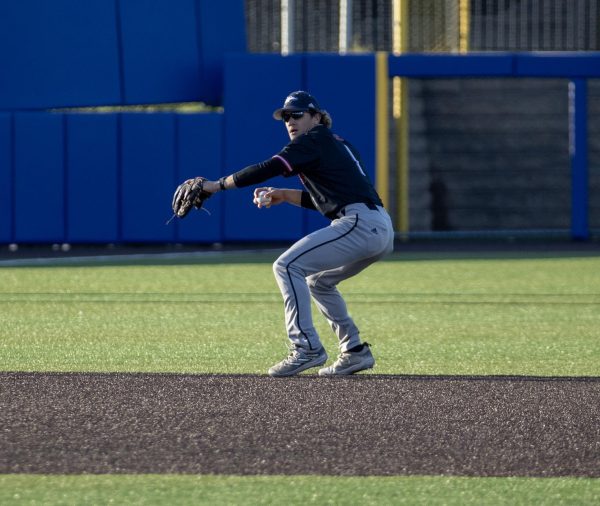

Senior Lauren Neslund clears the ball from danger Aug. 9, 2017 during NIU’s exhibition match against Drake University.

November 20, 2019

DeKALB — For Lauren Neslund, the road to being a starting center back on the women’s soccer team has been far from easy, as she’s dealt with adversity every step of the way.

Neslund, a captain and starting defender for the women’s soccer team, has dealt with a torn ACL in high school, little playing time her first year at NIU, inconsistent playing time her sophomore year and the same injury all over again her junior year.

{{tncms-inline alignment=”center” content=”<p>&ldquo;To be a defender, you have to be the best in her mind, so I knew that I had to work hard,&rdquo; Neslund said. &ldquo;I&rsquo;d ask [Colhoff] what I needed to work on, and I just tried to do that over the summer to be prepared and be ready for her.&rdquo;</p>” id=”2149189d-030f-41af-ba9e-58c4f33f48e0″ style-type=”quote” title=”Neslund” type=”relcontent” width=”full”}}

Neslund’s path to NIU started when she was young. She attended NIU’s summer ID camps in middle school. By her sophomore year of high school, NIU was scouting her and within the next year, she was committed to the Huskies.

NIU was an easy choice for Neslund. She’s from St. Charles, and attending NIU allowed her to remain close to her family, whom she shares a close relationship with. Neslund’s father has been a major role model for her.

“He’s really hard working and taught me that nothing is given to you,” Neslund said. “You have to work for it.”

The first thing her teammates bring up when talking about Neslund is her work ethic.

“She doesn’t need anybody standing there and telling her to go,” junior defender Madison Kaufmann said. “She just has that in her head to do it on her own, whether there’s a million people watching or none.”

Neslund rarely saw the field during her first year with the team in 2016. She appeared in only eight of 21 games for the Huskies, as the team was competitive and opportunities where hard to find.

By her sophomore season, she began to find her rhythm with the team. Neslund saw action off the bench, coming in to play 15-minute stretches during the 16 games she played.

Coming off a productive season in year two, Neslund was excited for her junior season. NIU hired Head Coach Julie Colhoff, a former Loyola University – Chicago player. Neslund felt like it was her time to prove herself as a player, but her junior year would be derailed before it even started.

“I was defending one of the forwards, and she spun me,” Neslund said. “I was going to trip her because I didn’t want her to beat me. I was reaching, and she just ran over my leg, and it popped.”

Pop. With the unwelcomingly familiar sound and sensation, Neslund knew her season was over. She had torn her right ACL.

“I was crying,” Neslund said. “I was on the ground. That pop, it just brought me back to when it happened many years ago. I was freaking out.”

The all-too familiar sound of the rupture brought her back to high school when she tore the ACL in her left knee. Now she had torn the other one.

She had bounced back from her first knee injury, but that was at the less demanding high school level. She was a Division I athlete now. Neslund knew the road ahead of her would be much harder, and she was unsure how she would come back.

The defender began her physical therapy the day of her surgery, with her trainer starting her on a mini bike machine to keep her leg moving. She progressed from there to a larger bike, balancing exercises and leg lifting exercises.

Depending on the nature of the injury and the person, ACL recovery periods generally last anywhere from six months to a year. Neslund was back to doing soccer activities in five months.

“Her rehab and work ethic to recovering is probably the best I’ve seen in my whole career as a coach, and unfortunately I’ve seen lots of [ACL injuries],” Colhoff said. “In terms of work ethic, it’s pretty much unmatched when it comes to Neslund. She came back in the spring and was still one of the first people to pass the fitness test even though she hadn’t played in months.”

The first day Neslund was cleared for soccer activity just passing the team’s fitness test. The team’s fitness tests consist of two drills: the “beep test,” where an athlete has to run 20 meters down and back before the beep goes off. The amount of time to achieve this task gets shorter after every beep. The players have to reach level 17.1 to pass it. The second drill is the “cones test,” with five cones set up five yards apart from each other. The players have to make the first seven shuttles in 35 seconds with 35 second break and then the last three in 40 seconds with 40 second break.

Colhoff wanted to work her back into the game slowly to prevent another injury, designating her for non-contact drills in practice. The practices gave the Huskie time to improve on the technical skills that weren’t really her strengths.

While the injury was devastating, Neslund has come to look at how everything unfolded in a new light.

“I think it’s given me more confidence,” Neslund said. “I knew it was going to be hard coming back to play at this level and the way that I surprised myself. We had fitness testing in the spring, and just coming off not being able to run or really work out, and I passed it the first time. Just surprising myself by doing things I didn’t really think I could do before, I think it just gave me more confidence on the field.”

Her work ethic and confidence caught the attention of her coach. Colhoff gave her a starting spot.

“To be a defender, you have to be the best in her mind, so I knew that I had to work hard,” Neslund said. “I’d ask [Colhoff] what I needed to work on, and I just tried to do that over the summer to be prepared and be ready for her.”

“She’s super diligent about how she is in the weight room,” Colhoff said. “She’s super diligent about how she is with nutrition. She sees the full picture, and I think she’s a good example of not only what it takes to come back, but to come back at the level you need to have to make an impact.”

Neslund’s time at NIU has gone by fast. She doesn’t feel like she’s a senior, but being one of the seniors on the team, the team’s younger players look up to her. She’s recognizing that her words and her actions mean more, as she is looked to as a leader.

Kaufmann saw Neslund’s leadership firsthand. Kaufmann was recovering from a broken kneecap around the same time Neslund was recovering from tearing her ACL.

“When we were here in the training room, we were in there together, and I always saw her biking,” Kaufmann said. “She brought a stationary bike out [to the soccer field] and so then I was like ‘Oh, I should be biking.’ So then I got that after her. She went to the weight room more times than she had to, so I looked up to her with that and went to the weight room more.”

Neslund would not only lead by example, but she’d push her teammates to get the most out of their workouts.

“The entire time she’s working her butt off and pushing me when I would slow down or get tired,” Kaufmann said.

Neslund’s experience at NIU can be used to motivate her younger teammates who are the future of the team. She has shown what it takes to make an impact on the team, despite not playing much early in her career.

“The biggest thing is showing people what sacrifice looks like,” Colhoff said. “A lot of people want to be Division I athletes. Everybody wants to win championships. I think Neslund is a good example of a player [who’s] willing to make sacrifices to get there, which is really important for young players coming in.”

Looking back at her time at NIU, Neslund pondered what she has taken away from her time as a Huskie. All the hours spent working on her abilities like workouts, drills, dieting, rehabbing and leading, have led her to where she is today.

“The biggest thing I learned was never giving up, even if your work isn’t being recognized; it doesn’t matter,” Neslund said. “Keep working, ‘cause your time will come eventually, and you want to be ready for when it does come.”