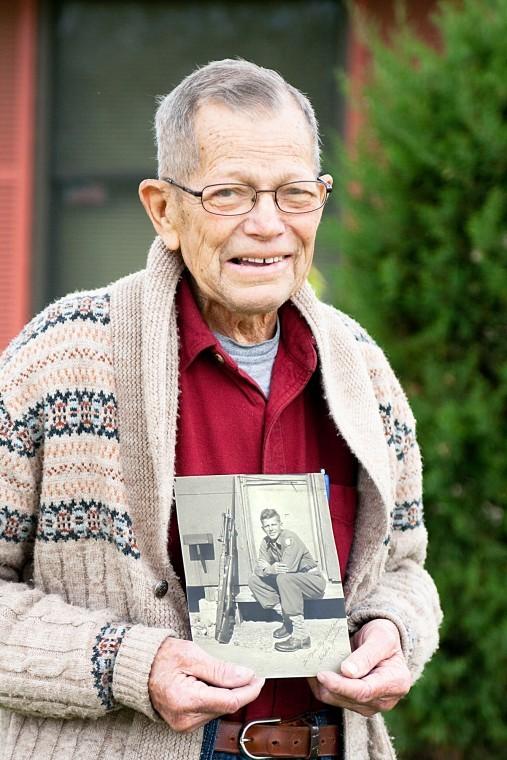

Retired professor, WWII veteran takes Honor Flight to D.C.

April 22, 2012

While sitting in his living room, World War II veteran Hallie Hamilton clenched a blue and white paisley handkerchief. Occasionally, he would bring the handkerchief to his face and use it to blot away tears.

As he reflected on his emotional visit to the World War II Memorial in Washington, D.C., a wave of nostalgia overcame Hamiliton. The trip, which was organized by Honor Flight Chicago, reminded the 88-year-old DeKalb resident of the experiences he had almost 70 years ago.

The retired NIU journalism professor was one of 94 World War II veterans who recently traveled to Washington, D.C., for a free one-day trip. Mary Pettinato, Honor Flight Chicago CEO and founder, said the non-profit organization has flown 3,081 World War II veterans in 36 Honor Flights since June 2008.

Hamilton visited the Iwo Jima Memorial, Lincoln Memorial, Korean War Veterans Memorial, Vietnam Veterans Memorial, and the World War II Memorial. He said it was an exciting trip, but it was also tiring. The veterans arrived at Midway Airport at 4:30 a.m. and didn’t return until 9 p.m.

“I try to exercise every day, but I wasn’t ready for the Olympics,” Hamilton said as he chuckled to himself.

‘I tear up just talking about it’

When Hamilton stood in front of the World War II Memorial for the first time, he was in awe. Before him were 4,000 stars. Each star represents 100 Americans that died during the war.

Looking up at those stars was a poignant reminder for Hamilton of the friends and people he met in the war that didn’t make it home alive.

“Oh gosh, yes, it was very emotional,” Hamilton said. “I tear up just talking about it.”

Hamilton said he was also thinking about the 200 men he traveled to Italy with on an “ex-leisure ship.” They all received different assignments and parted ways.

“I suppose I was thinking about people I’d known and things I’d experienced in different places,” he said. “I was probably wondering what happened to them and wished they were there.”

An unforgettable mail call

The U.S. Army drafted Hamilton in March 1942. He trained infantrymen in Fort McClellan, Ala., and spent one and a half years in the U.S. The remaining one and a half years of his service were spent in Italy, where he trained infantry soldiers for the D-Day Invasion and worked as a guard at a prison.

During his deployment, Hamilton would sometimes wait for long periods of time to hear from his family. He yearned to hear his name yelled during “mail call.”

Almost seven decades later, Hamilton received a mail call he probably will never forget. While on the flight back from Washington, D.C., each veteran was given a bag of letters.

Hamilton’s wife Floann said her husband received more than 133 letters from family, friends, former students, professors, President Barack Obama, Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel and many others. Hamilton taught at NIU for 33 years before retiring in 1991, which made the letters from his former students especially meaningful to him, she said.

“He was 19 when he went to war and is 88 now, so the tribute was a long time coming,” Floann said. “Some of his former students said his teaching influenced their life and career. That meant a lot.”

Even though Hallie can’t remember what is written in each letter, he said they were all “complimentary” and “very, very sweet.”

“I think about those letters and tear up,” Hallie said. “I want to tell someone about who each person is and what role they played in my life.”

‘Do you want a ride soldier?’

When Hamilton and the other veterans returned to Midway Airport, their family and friends greeted them with posters as bagpipers and a band played in the background.

It was a moment for Hamilton that was a stark contrast to the reception he received after he was discharged from the army.

Hamilton said a boat dropped him off in New York, and the army gave him some cash for public transportation. After that, there was no one waiting for Hamilton. He was expected to make the trip back home on his own.

Hamilton bought a train ticket to Vincennes, Ind., and fell asleep sometime during the 900-mile trip. He missed his stop by about 100 miles and ended up in Evansville, Ind.

“I told the conductor, ‘I slept through my stop. How do I get back?’ The conductor said, ‘Don’t worry I’ll get you a train,’” Hamilton said.

After arriving back in Vincennes, Hamilton was dismayed to discover that there was no public transportation available that would get him to Bridgeport, Ill.

Wearing his winter army coat, and carrying all of his personal belongings, Hamilton started walking and hitchhiking to his hometown, which was about 236 miles away.

Hamilton said people driving by knew he was a serviceman by what he was wearing, but no one was in a big hurry to pick him up. Finally, he was able to get some rides with people who were passing through.

When he got to a bridge, Hamilton put his bags down as a car pulled up alongside him. A lady stopped and with a smirk asked, “Do you want a ride, soldier?”

“It was my mom,” Hamilton said with his voice quavering. He paused for a moment and used his handkerchief to wipe away the tears that were streaming down his cheeks.

Before embracing his mother, Hamilton asked just to make sure, “Is that you, mom?”

Hamilton dabbed his tears, folded his hands on his knee, and looked straight ahead.

“And that’s the story of how I got home the first time,” he said with a smile.