Recognizing Black athletes of the pre-Civil Rights era

Black History Month is a time for recognizing the impact Black Americans have had on the U.S. While this month is too short to fully appreciate all the history, accomplishments and sacrifices, it’s important to use this time to bring attention to and educate people on Black history and issues in the Black community.

For the month of February, I’ll be writing columns on important Black athletes and their accomplishments to further the movement for equality, the integration of pro sports, shedding light on overlooked issues in their communities and representing the true American spirit of standing up for one’s beliefs.

My only hope is these American heroes are remembered, appreciated and talked about, not only during Black History Month, but every day, long after we are all gone.

It’s important to look back at the Black athletes who paved the way for others to have a place in professional sports. This column is dedicated to those of the pre-Civil Rights era.

Breaking the color barrier

For many of us, I assume it may be hard to imagine at time where sports were segregated. However, some Americans alive today can recall a time where sports were segregated, because unfortunately, it wasn’t all too long ago in America’s history.

Jackie Robinson (1919-1972)

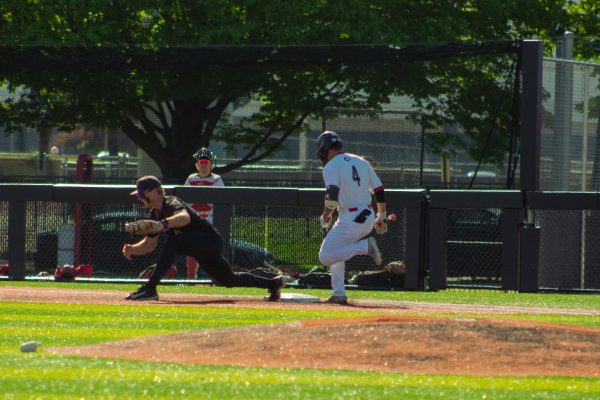

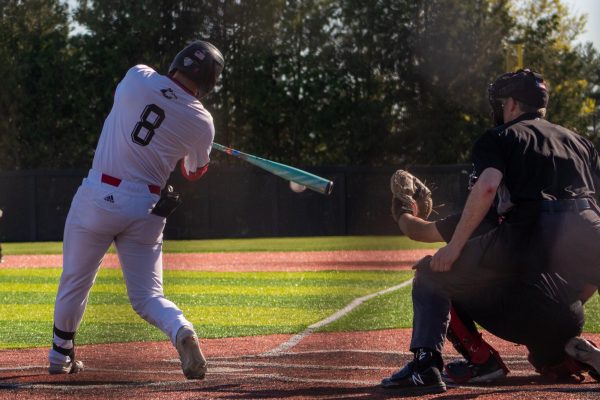

Jackie Robinson was a professional baseball player from Cairo, Georgia. He was the first Black American to play in the MLB’s modern era. His professional career began in 1945 with the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro American League.

In 1945, Brooklyn Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey signed Robinson to play for the Montreal Royals of the Class AAA International League for the 1946 season. By April 15, 1947, Robinson was playing for the Dodgers in the majors. He primarily played at second base.

Over his career, Robinson would push for greater integration in the MLB. He famously called out the New York Yankees in 1952 for not breaking the color barrier on their own roster, despite the Dodgers having done so in 1947. By 1959, the entire league became integrated after the Boston Red Sox signed Elijah Green.

Robinson would go on to play from 1947 through the 1956 MLB season. He retired with 137 home runs, 734 RBIs, 197 stolen bases and a .311 batting average.

His accolades include the 1949 National League MVP, 1955 World Series championship, six-time All-Star, two-time stolen base leader, 1949 batting champion, 1947 MLB Rookie of the Year, Baseball Hall of Fame class of 1962 and his number 42 being retired by not only the Dodgers, but the entire league.

After baseball, he became involved in business and continued working as an activist for social change. He was an executive for Chock Full O’ Nuts coffee company and had a part in forming the Black-owned Freedom Bank.

For the rest of his life he supported civil rights movements and other Black athletes. He served on the NAACP board until 1967. He died from heart and diabetes complications on Oct. 24, 1972.

Jesse Owens (1913-1980)

Jesse Owens was an American track and field athlete from Oakville, Alabama. Owens became one of the most accomplished track and field athletes in American history over his career, winning several events at all levels of competition, and breaking several world records.

Owens competed for the Ohio State University on its track and field team. On May 25, 1935, while competing at the University of Michigan, Owens equaled or broke four world records in sprinting, hurdles and long jump.

Owens is best known for his participation as a member of the U.S. Olympic team at the 1936 Berlin Olympics. There, Owens would win four gold medals. Adolf Hitler began to stop publicly congratulating the athletes after receiving pressure from the International Olympic Committee to recognize all athletes.

While many believe it was due to Owen’s success based on inaccurate reporting, Hitler stopped attending the medal ceremonies prior to Owen’s first win. Hitler shunned a different Black athlete the first day of events, which led to him not attending ceremonies after.

Owens did show the world Black athletes were equal to white athletes, destroying beliefs of Aryan superiority in athletics that was prevalent at the Olympics in Nazi Germany.

Unfortunately for Owens, he received little acknowledgement from American leaders upon his return home. Former President Franklin D. Roosevelt never publicly acknowledged his accomplishments, or invited him to the White House. Finally, in 1955, former President Dwight D. Eisenhower named Owens Ambassador of Sports to honor him for his accomplishments.

After his days as an athlete, he spent a lot of his time working with underprivileged youth. He moved to Chicago in 1949 and started a public relations firm. There, he spent many years as a popular jazz disc jockey. He also became the director of Chicago’s Boy’s Club.

He died March 31, 1980 due to lung cancer in Tucson, Arizona. He was buried in Chicago.

Earl Lloyd (1928-2015)

Earl Lloyd was a professional basketball player and coach from Alexandria, Virginia. Lloyd was one of three Black players taken in the 1950 NBA draft, and the first Black player to play in an NBA game. He played small forward during his nine-year career.

Lloyd was drafted 100th overall in the ninth round by the Washington Capitols, and made his NBA debut Oct. 31, 1950, scoring six points. He played seven games for the Capitols before the team folded midseason on Jan. 9, 1951.

After the team folded, he was drafted into the U.S. Army, and served time fighting in the Korean War. While serving in the Army, the Syracuse Nationals, known today as the Philadelphia 76ers, claimed him off waivers. He would return to the NBA in 1952 for the 1952-53 NBA season.

He averaged career-highs in points and rebounds during the 1954-55 season at 10.2 points-per-game and 7.7 rebounds-per-game. The Nationals would go on to win the 1955 NBA Championship, making Lloyd the first Black player to win a title.

On June 10, 1958, he was traded to the Detroit Pistons, where he would finish his career and retire after the 1959-60 season. Lloyd finished his 560-game career with 4,682 points, 3,609 rebounds and an induction in the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame in 2003.

In retirement, Lloyd became the first Black assistant coach in the NBA with the Pistons, later becoming the head coach for the 1971-72 season. He worked as a scout for the Pistons, discovering future NBA All-Stars Willis Reed, Earl Monroe and Bailey Howell.

After leaving the NBA, Lloyd worked as a job placement administrator for the Detroit public school system. During that time, he ran programs teaching job skills to underprivileged youth.

Lloyd retired to Fairfield, Tennessee until his death on Feb. 26, 2015.

Other important pre-Civil Rights era Black athletes:

Jack Johnson became the first Black heavyweight boxing champion in 1908.

Lucy Diggs Slowe became the first Black woman to win a major sports title, the American Tennis Association’s first tournament in 1917. She also founded the first Black sorority in 1908, Alpha Kappa Alpha, at Howard University.

Fritz Pollard of the Akron Pros and Bobby Marshall of the Rock Island Independents became the first Black NFL players in 1920. Pollard was also the first Black player to play in the Rose Bowl in 1917 with Brown University, and the first Black NFL coach in 1921 as co-head coach of the Pros, while playing running back.

Sherman Maxwell became the first Black sportscaster in 1929 with WJNR in Newmark, New Jersey. Maxwell would call Negro League baseball games, before becoming sports director at WWRL in 1942. He would go on in the 50s and 60s to write historical articles on the Negro Leagues and their players, in hopes of preserving their history for future generations.

Willie Thrower became the first Black quarterback in the post-World War II era NFL with the Chicago Bears in 1953.